Collective Intelligence in Grantmaking

What might collective intelligence mean for grantmaking?

Alongside asking how technology can better support collective design and decision making, we got stuck into some broader, more theoretical questions looking at the role of collective intelligence and collective wisdom in grantmaking.

Cassie Robinson commissioned this research as an exploration into the broader potential for collective intelligence in grantmaking, pushing at the boundaries of both how we think about participatory grantmaking and collective intelligence.

She asked us to address the following questions:

- What’s the role of collective intelligence in grantmaking?

- Where human intelligence is combined with machine intelligence, how and where might that be useful in grantmaking?

- What other kinds of intelligences of ways of knowing or intuiting could communities draw on when imagining, decision-making and deliberating?

- If collective intelligence was to grow into collective wisdom, how might that be developed during the grantmaking process?

The answers to these questions draw on a broad range of sources, from practical examples to speculative theories. They are designed to provoke discussion.

Tl;dr

Collective intelligence is already being applied to grantmaking organisations in a number of ways, but we’re far from getting the most out of it.

Collective intelligence can make grantmaking organisations more effective and more efficient. It can also do so much more than that. It can bring depth, breadth and plurality, and assign value differently. It can challenge dominant narratives and help us to see the world in a new light by including unheard voices and showing what the collective can know that an individual never can. It can help us to develop new ways of thinking and taking action together. It can harness a range of ways of knowing, from learnt knowledge and lived experience to the capacity to imagine and the ability to enact. By drawing on a range of intelligences, it can free us from temporal restrictions, help us to embrace the more-than-human world, and address injustices of the past, bringing the future into the present. It can redefine what grantmakers do, shifting them from being responsible distributors of funding for projects to investors and stewards of community infrastructure.

In this paper we run through different opportunities for collective intelligence in grantmaking, considering established methods and off-the-shelf products that could be adopted right now, how to expand the value we get from data, where different intelligences come into play, what working well as a collective looks like and how we can welcome in different futures.

We make six practical recommendations for grantmaking organisations:

- Automate repeatable tasks now! And let the humans do the hard stuff

- Fund community groups, not projects

- Become experts in group behaviour and group potential, and harness a range of intelligences to support communities to work together

- Start working with community groups at the scoping of possibility and problem definition stage, not solution stage

- Collect diverse forms of data and analyse it in novel ways

- Tear up your funding application forms

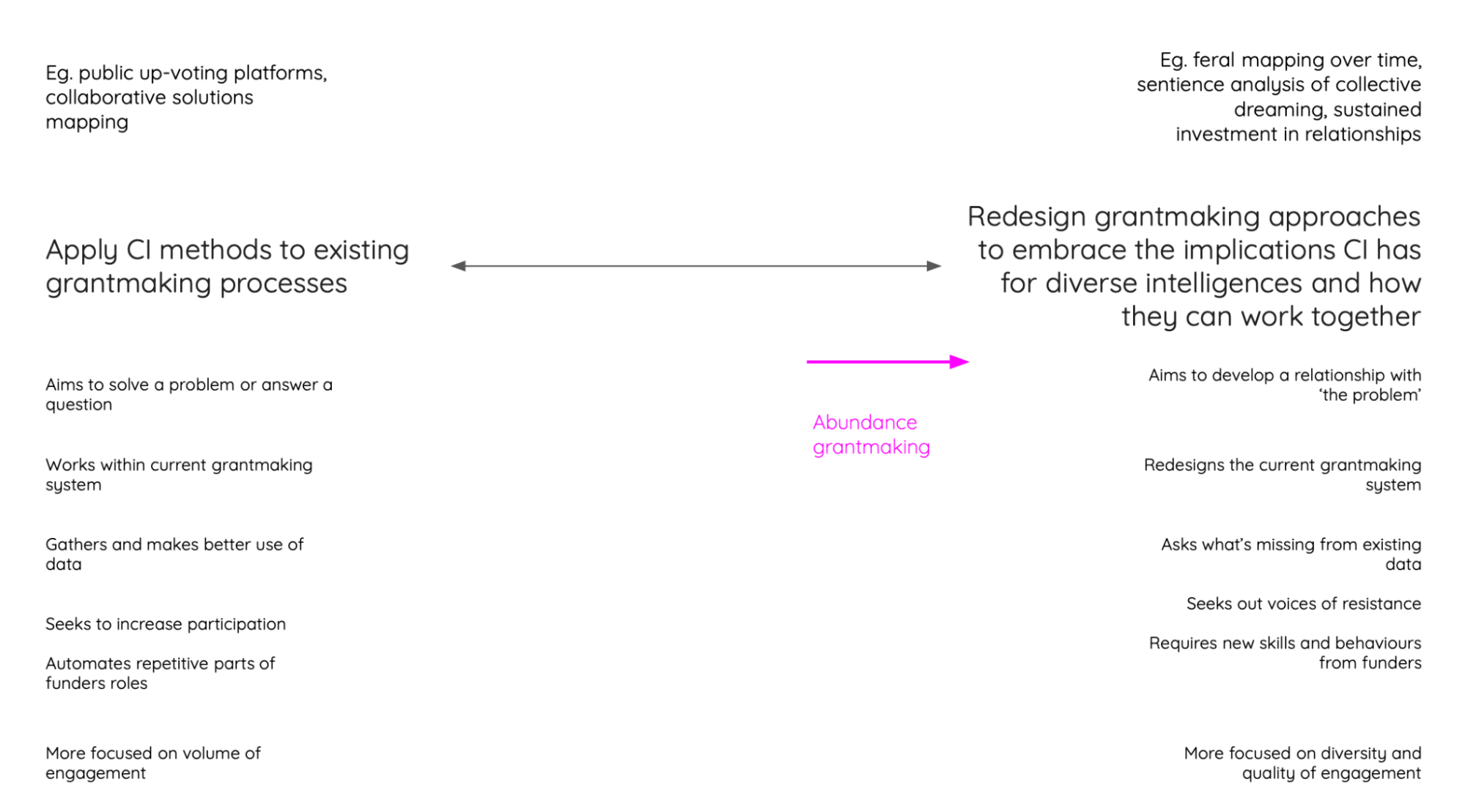

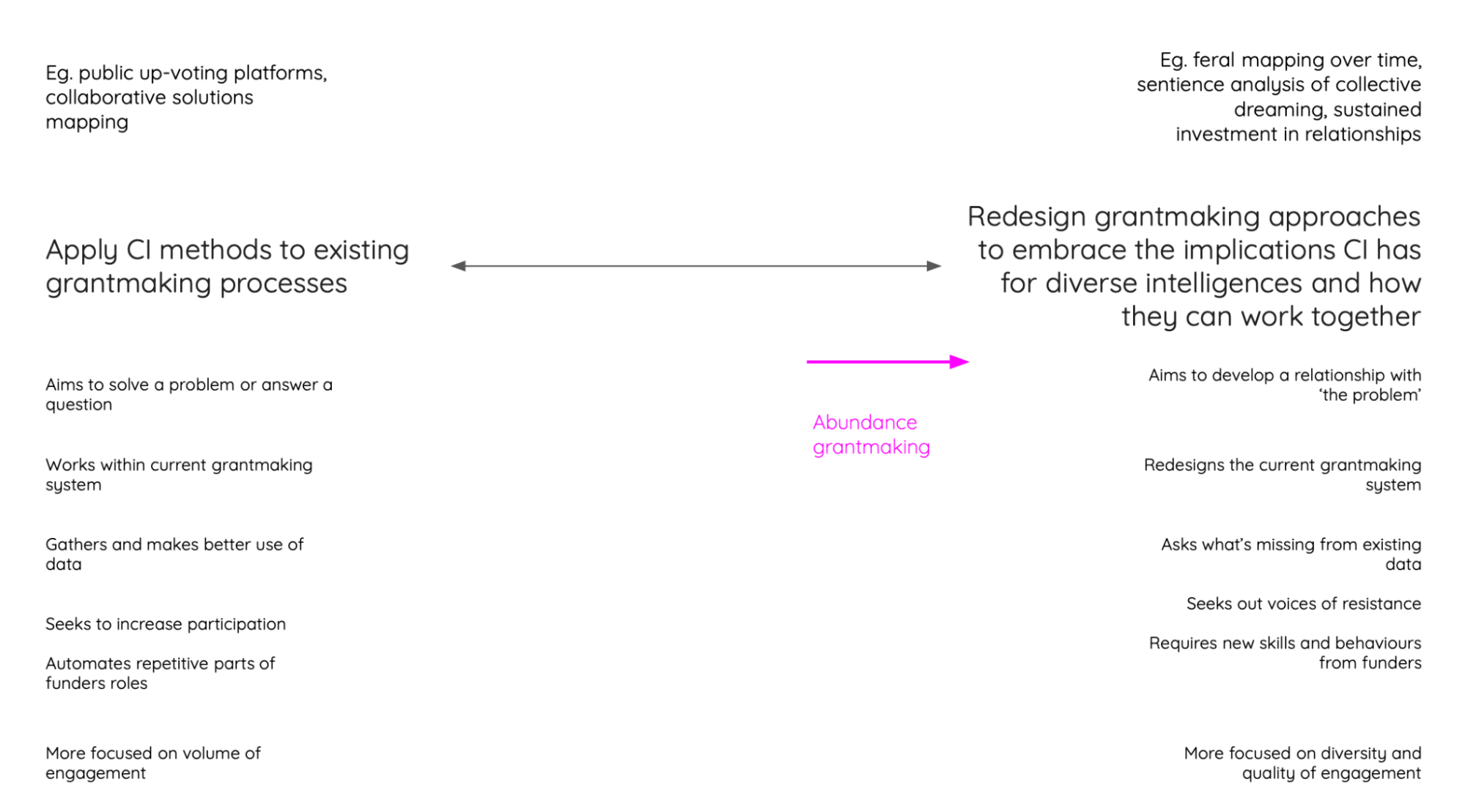

Taken together, we think of this approach as abundance grantmaking because it celebrates plurality and the entangled nature of the collective across ideas, people and the more-than-human world. It also challenges the notion of grantmaking as a zero-sum game where money is the most significant investment that grantmakers can offer. Thinking and working abundantly encourages grantmakers to recognise their capacity to steward change and scaffold community infrastructure through developing people and the relationships they have with one another.

Contents

- Challenges to grantmaking

- What’s the role of collective intelligence in grantmaking?

- When human intelligence is combined with machine intelligence, how and where might this be useful in grantmaking?

- What other kinds of ‘intelligences’ of ways of knowing or intuiting could communities draw on when imagining, decision-making and deliberating?

- If collective intelligence was to grow into ‘collective wisdom’, how might that be developed during a grantmaking process?

- References and resources

1. Challenges to grantmaking

Grantmaking organisations face a crisis of legitimacy on several fronts. Challenges and critiques centre around the ethics of throwing bad money after good, their function as a sticking plaster for unjust systemic inequality and the perpetuation of such inequality due to the lack of diversity among organisational boards and employees. Comprehensive and high-profile critiques such as those from Anand Giridharadas, Edgar Villeneuva and the UK’s Civil Society Futures inquiry are combined with a growing scepticism towards a perceived elusive and shady elite amongst some sections of the population, of which ‘big philanthropy’ forms a part.

In response to this many foundations are engaged in deep soul searching, asking questions about the distribution of power, justice and representation, the aims and ethics of their investments, the time-frames on which they operate and the relationship they have with the public sector.

A popular way to address some of these challenges has been to develop a more participatory approach by involving the communities receiving funding in the design, decision-making and allocation of awards. Participatory grantmaking—and the range of funding models that fall under this umbrella—is growing in popularity across the world, from The Other Foundation’s work supporting LGBTQ people across southern Africa to pan-European activist funding network, Fund Action. There have been repeated calls for philanthropic organisations to recognise the value of greater participation and to be bolder in shifting power into the hands of the communities they aim to support. The question then, is not whether to do this, but how. And while most efforts focus on centering and prioritising lived experience, and on how to encourage more people with lived experience into the existing philanthropic structures of committees, boards and leadership teams, there is an emerging field that more effectively acknowledges the complex interaction of experience and expertise, offering greater transformational potential: collective intelligence.

2. What’s the role of collective intelligence in grantmaking?

Collective intelligence combines the useful things that technology can do with the unique things that humans can do. By combining different viewpoints and skills, a group of people together can achieve things that a single person can’t. This makes collective intelligence a critical tool for tackling the highly complex, interrelated issues that philanthropic bodies are concerned with, such as poverty, climate change or a global pandemic, all of which require people to think and act together across communities, nations and the globe.

Nesta’s Centre for Collective Intelligence Design describes it as:

The enhanced capacity that is created when people work together, often with the help of technology, to mobilise a wider range of information, ideas and insights.

MIT’s Centre for Collective Intelligence describes it as:

How people and computers can be connected so that—collectively—they act more intelligently than any person, group, or computer has ever done before.

It draws on the idea that all knowledge is situated and partial; that is, it is constructed by a person whose experiences cause them to approach an issue in a certain way (Haraway 1988). One person alone can only hold part of the picture of any given situation. Many people together, with diverse viewpoints and experiences, can get a more complete picture of that situation and discover more effective ways to solve problems. By combining different viewpoints and different skills, a group can achieve things that a single person can’t.

From guessing the weight of an ox to Wikipedia, groups of people time and time again achieve more accurate and more impressive outcomes than any one person alone (Kendell 2016). Advances in technology are helping people work together in new ways, whether that’s to monitor state surveillance in New York, estimate the likelihood of genocide or idenitfy new galaxies.

Collective intelligence can describe a group of six people working together in a room. It can also describe hundreds of thousands of people working together across the world. It’s critical for tackling highly complex, interrelated issues such as poverty, climate change or a global pandemic, which require people to think and act together across communities, nations and the globe.

The growth of collective intelligence demands a humility shift on the part of many institutions. In a world that embraces collective intelligence their role is less to prescribe and deliver solutions than it is to coordinate and steward collective action.

Grantmaking bodies already use some collective intelligence methods, though they might not recognise them as such.

- The SOUP funding network is an example of a grassroots network that uses collective intelligence in the form of crowdfunding and collective decision-making to raise money and allocate micro-grants to community organisations. Blind shortlisting (where names and organisations are removed) happens online, by volunteers from the locality. The winner is voted on at an in-person event, with a soup dinner. SOUP believe in building a forum for critical listening and empathy exchange. They aim for outcomes at an individual, community and global level.

- Nesta Challenges supports governments and funding bodies to design mission-driven challenge prizes to solve specific problems. By using a challenge prize model, funders aim to drastically broaden the range of potential solutions and gather novel or unexpected approaches. Recent challenges have included designing materials to construct affordable cool roof systems in Sub-Saharan Africa, solutions to antimicrobial resistance and building resilience in communities in London during the Covid-19 pandemic.

- In 2014 a small group of funders started an open grants movement by publishing funding data going back to 2004. This enabled organisations like 360 Giving to push for greater transparency from other funders, aggregating funder data on their open platform. This helps funders see where their efforts sit within the wider landscape of funding so that they can make more informed, effective and strategic funding choices. It also helps grant recipients and the general public see what is being funded and what’s not.

Like these examples, most applications of collective intelligence in grantmaking are about applying established collective intelligence methods to existing processes in order to become more effective at tackling problems. There are many more established methodologies that could be applied to different stages of the grantmaking process. These include things like broader use of deliberative processes, citizen data collection and community solution mapping.

Nesta’s Centre for Collective Intelligence Design identifies four distinct applications of collective intelligence that could help funders encourage more participation with the communities that matter to their work:

- Understand problems: Generate contextualised insights, facts and information on the dynamics of a situation. (Eg. Crowdsourcing datasets, both quantitative and qualitative.)

- Seek solutions: Find novel approaches or tested solutions from elsewhere, or incentivise innovators to create new ways of tackling a problem. (Eg. Crowdsourcing ideas, solutions mapping, challenge prizes.)

- Decide and act: Make decisions with, or informed by, collaborative input from a wide range of people and/or relevant experts. (Deliberative platforms, upvoting, weighted voting, well-facilitated community events.)

- Learn and adapt: Monitor the implementation of initiatives by involving citizens in generating data, and share knowledge to improve the ability of others. (Gathering data, analysing data, reframing narratives around that data.)

These methodologies can easily be applied to different stages of the grant-making process and are detailed in the Collective Intelligence Design Playbook and this guide to good group decisionmaking.

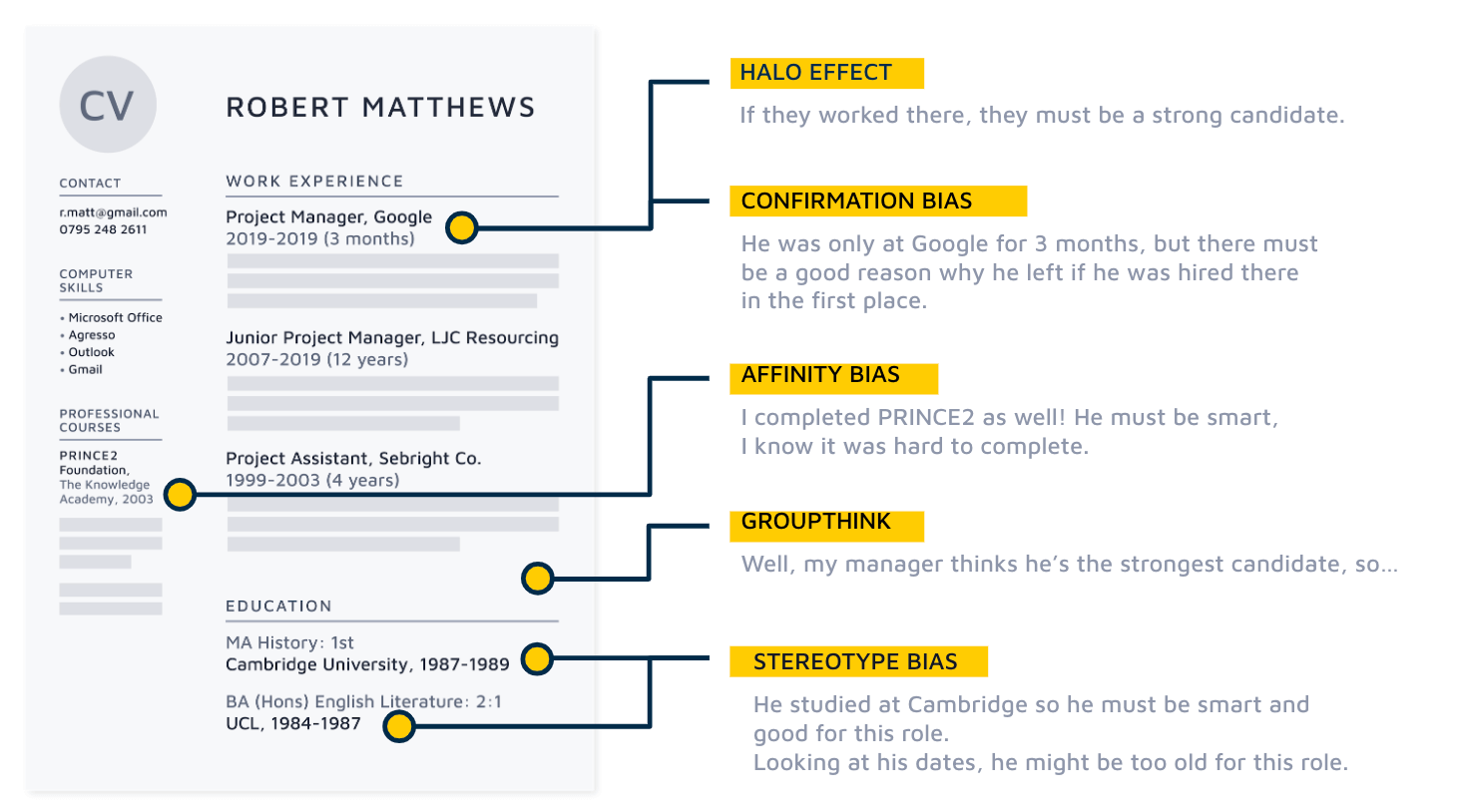

“At the simpler end of the spectrum, grant makers could become more collectively intelligent by involving a greater diversity of people in review processes and thinking about how decision-making meetings are run to minimise biases like groupthink,” says Kathy Peach, Director of the Centre for Collective Intelligence Design at Nesta. “You could also use collective intelligence tools to involve communities in identifying or prioritising the issues that matter most to them before a request for proposals is even drafted. You could bring together local communities and experts to develop more robust, locally-appropriate solutions and incorporate social accountability tools into project evaluation, allowing communities to report on implementation and impact in real-time.”

According to Peach, there are two barriers preventing grantmakers from benefiting from these methods. “Funders need to invest in the design and support for good collective intelligence processes—something few do at present. And, just as critically, they must be clear about the extent to which they are genuinely willing to open up the process to influence from outside their institutions.”

In this way, collective intelligence methods can help funders improve their efficiency by letting humans focus on what they do best and letting machines do the rest. They can also help funders improve their effectiveness by drawing on a broader range of viewpoints to build a more accurate picture of a problem and potential solutions. What’s more, they start to provoke a shift in the power dynamic between the funder and the communities they serve.

The potential of collective intelligence for grantmaking goes beyond these methods and could have deep implications for how funders think about and execute their work. This is where it starts to get exciting. It involves reevaluating the role of data, embracing the power of different intelligences and understanding what working together as a collective means.

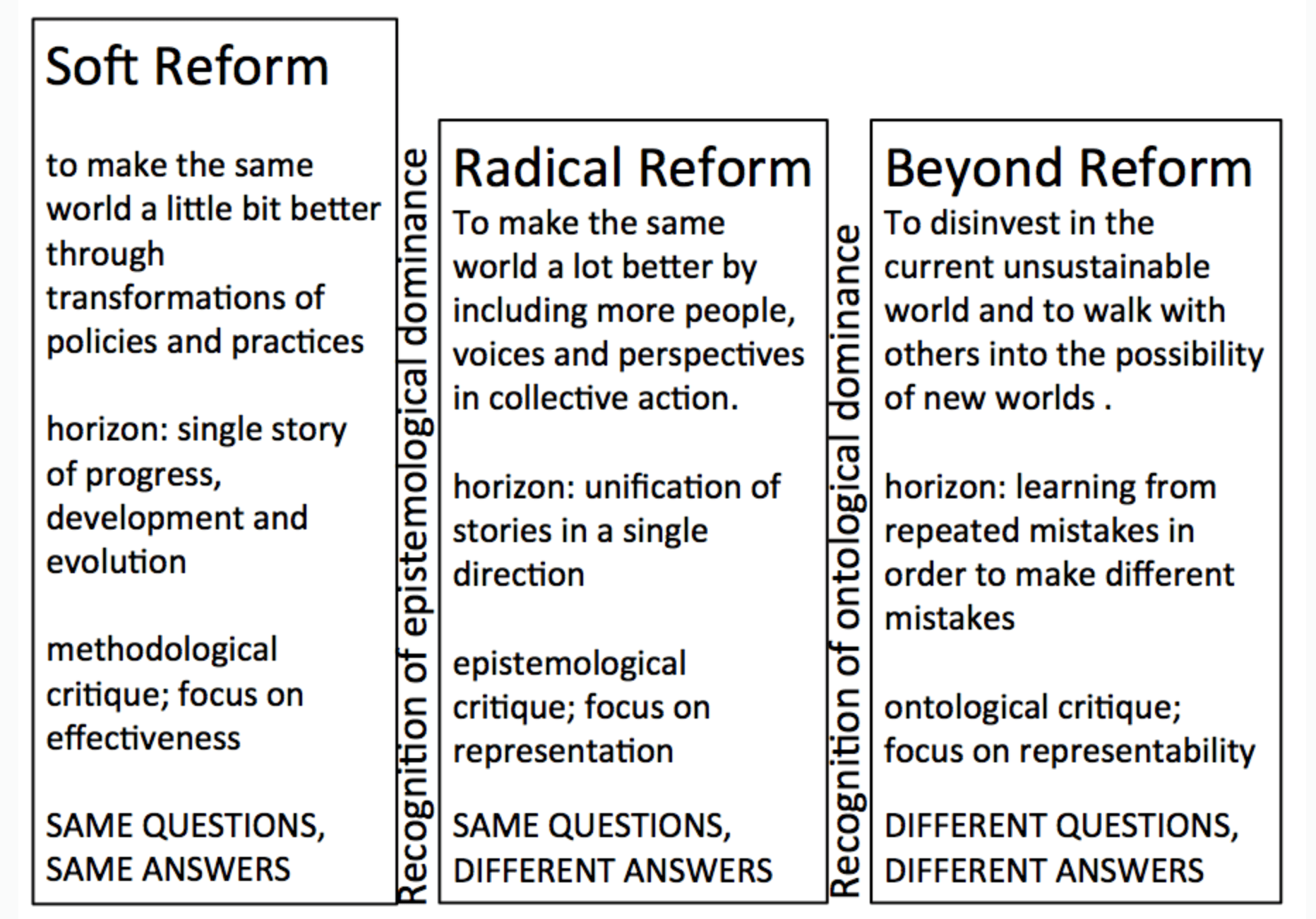

At one end of the scale, grantmakers can use collective intelligence to enhance their existing processes. At the other end they can use collective intelligence to make even more transformational changes to the way they work.

If funders want to see transformative change in the communities they work with, there is the potential through this thinking to reframe the funder role from being responsible distributors of programme funding to being the stewards of relational community infrastructure. This requires deep behavioural and structural change within grantmaking organisations. It starts to move from collective intelligence towards what we might think of as collective wisdom.

3. When human intelligence is combined with machine intelligence, how and where might this be useful in grantmaking?

Collective intelligence has the potential to help grantmakers be more effective by bringing a greater number of diverse viewpoints around an issue. It can help grantmakers become more efficient by automating administrative tasks so that people can work together easily. Collective intelligence should also provoke grantmakers to reevaluate how data is used and the value it holds.

Technology for intelligence

One way to increase the collective intelligence of a group is by increasing the volume of the group, adding more diversity and skills by appealing to the wisdom of the crowd. We no longer have to wait for people to attend a county fair to view the weight of the livestock; we have the technology to mobilise large numbers of people across different geographies faster than ever before.

The social sector often acts with a healthy scepticism towards technology, rooted in the recognition that deep work happens at a person-to-person level. Making the most of technology, however, is fundamental for organisations exploring collective intelligence. Let people do things that only we can do—moral and ethical judgements, subjective interpretations of performance and situations—and use machines to do the rest.

Many useful tools and platforms that could easily be applied to different parts of the grantmaking process already exist.

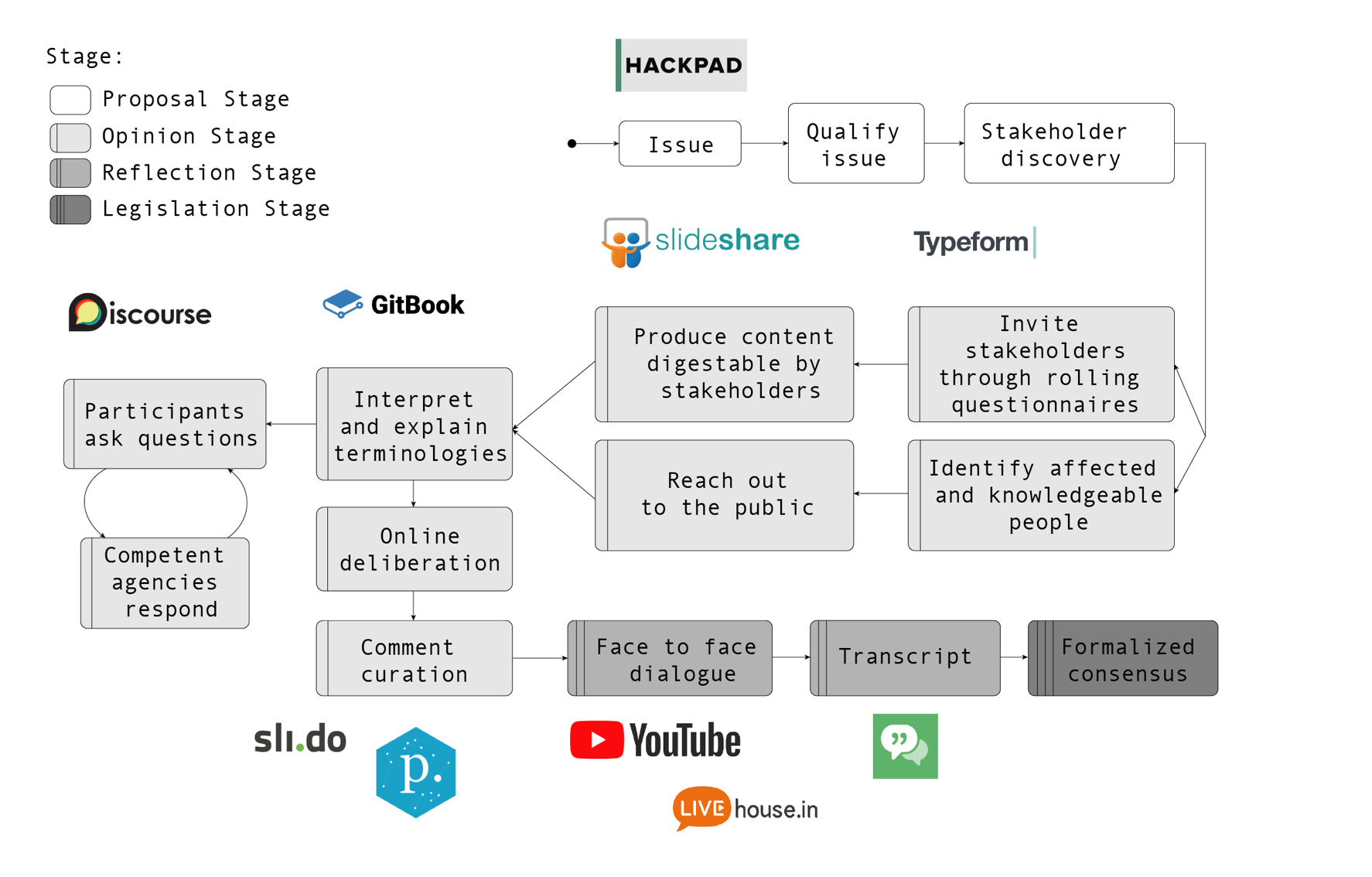

Take vTaiwan for example, an experiment in having national conversations about pertinent issues online. They use a range of online platforms, such as Discourse, Polis, Sli.do and YouTube for the four stages of the deliberation process. These existing tools could be picked up by grantmakers wanting to have more open engagement in the programmes they fund.

Image: https://info.vtaiwan.tw

Another example of a tool that could provide inspiration for how technology can help the grantmaking process is Applied, a start-up attempting to disrupt the traditional job application process by limiting the opportunity for unconscious bias to facilitate the decision-making process. Instead of CVs, Applied asks candidates four highly targeted questions about their experience in different aspects of a role. The answers are then served up to reviewers in an anonymous and randomised order (ie. all the answers to question one first, followed by all the answers to question two in a different order, and so on). This encourages the content of each answer to be taken on its own merit. Applied’s analysis showed that sixty percent of candidates hired through the platform would have been overlooked in a traditional HR process. They were also more likely to come from underrepresented groups. We know that unconscious bias is as prevalent in decisions around funding allocation as it is in recruitment. What would taking an Applied approach as part of the grantmaking application look like?

Image: beapplied.com

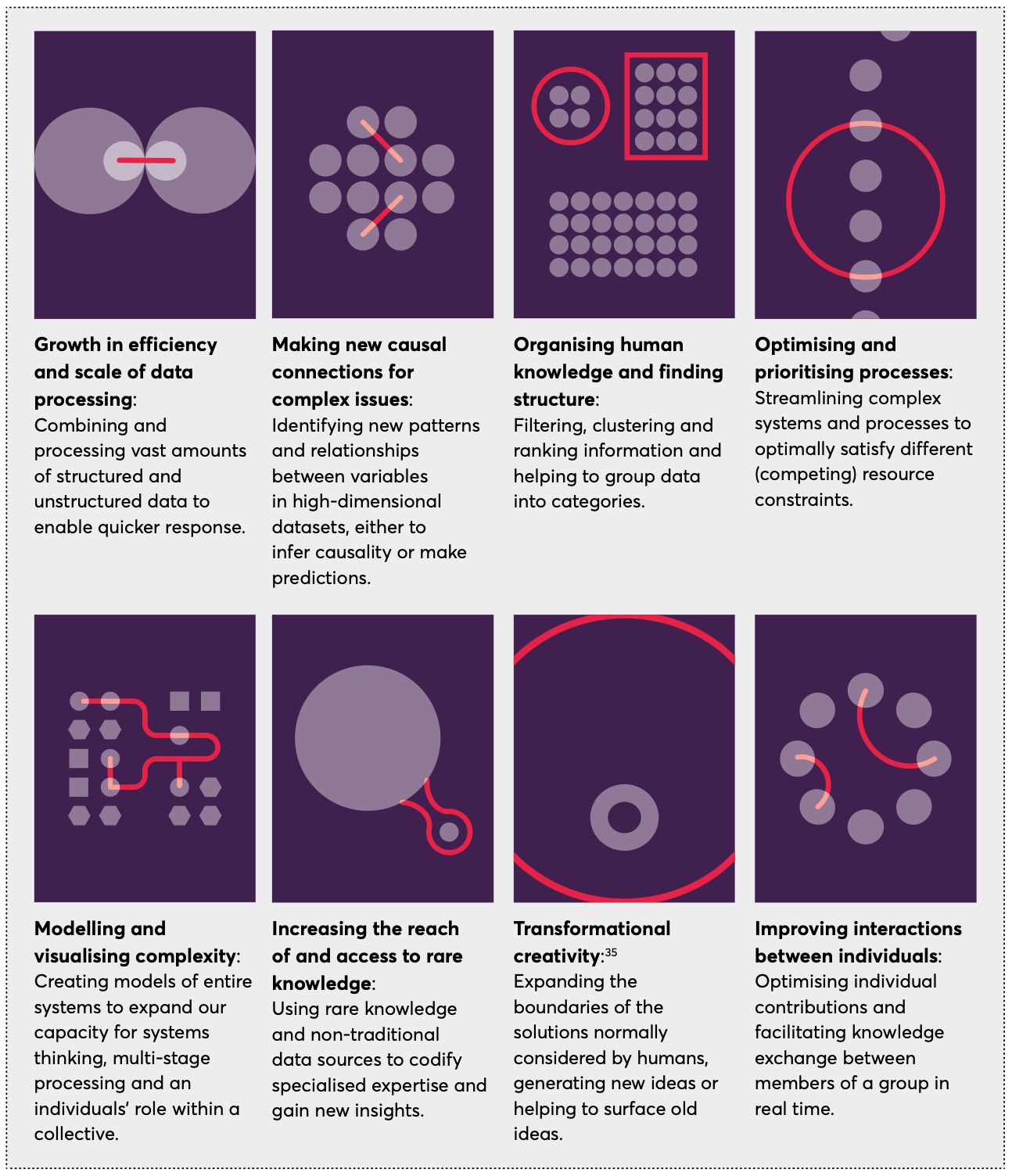

Machine intelligence takes this a step further. It uses large amounts of data, ‘read’ by an algorithm which sees patterns in that data and learns from the data as more is fed in. This requires a lot of data and data that is structured in such a way it can be processed by the machine. Algorithms need to be trained to read the data, which can be done either with existing datasets or by humans (for example, categorising types of animals in photos so the machine learns to recognise them.) This requires a significant technological overhead and, to be effective, for funders to be very clear on what it is they want the machine to do. For more inspiration, Nesta’s The Future of Minds and Machines report outlines the added value that machine intelligence can offer to collective intelligence.

Image: Nesta, The Future of Minds and Machine 2020

Any introduction of machine learning needs to come with deep considerations of the structural biases that may be being encoded into an algorithm. In her discussion of algorithmic injustice and relational ethics, Abeba Birhane points out, “Any data scientist working to automate issues of a social nature, in effect, is engaged in making moral and ethical decisions” (2021). Technical fixes can all too easily come at the expense of marginalised or data-invisible communities; precisely the people grantmakers tend to work with. Funders exploring the machine learning space need to work with people who are not just experts in data science, but also the ethics of algorithmic (in)justice. The work of Sasha Constanza-Chock and the Design Justice Network provides examples and strategies for inclusive, just design practice (2020).

That’s not to say that there’s no potential for machine learning within a grantmaking context. When thinking about the potential of machine learning, all funders need to ask the critical questions of what is best done by humans and what could be done by machines? Moral and ethical judgements, subjective interpretations of performance and situations generating few examples or data, are squarely in the realm of human consideration. When it comes to large scale datasets and consistent interpretations of performance, there may be scope to introduce machine intelligence.

It could, for example, be deployed to look for patterns in grantmaking applications and outcome data from projects. As grantmakers become more confident and skilled in their use of technology we could see experiments in awarding microgrants through an intelligent programme (with or without human oversight, or keeping a ‘human-in-the-loop’).

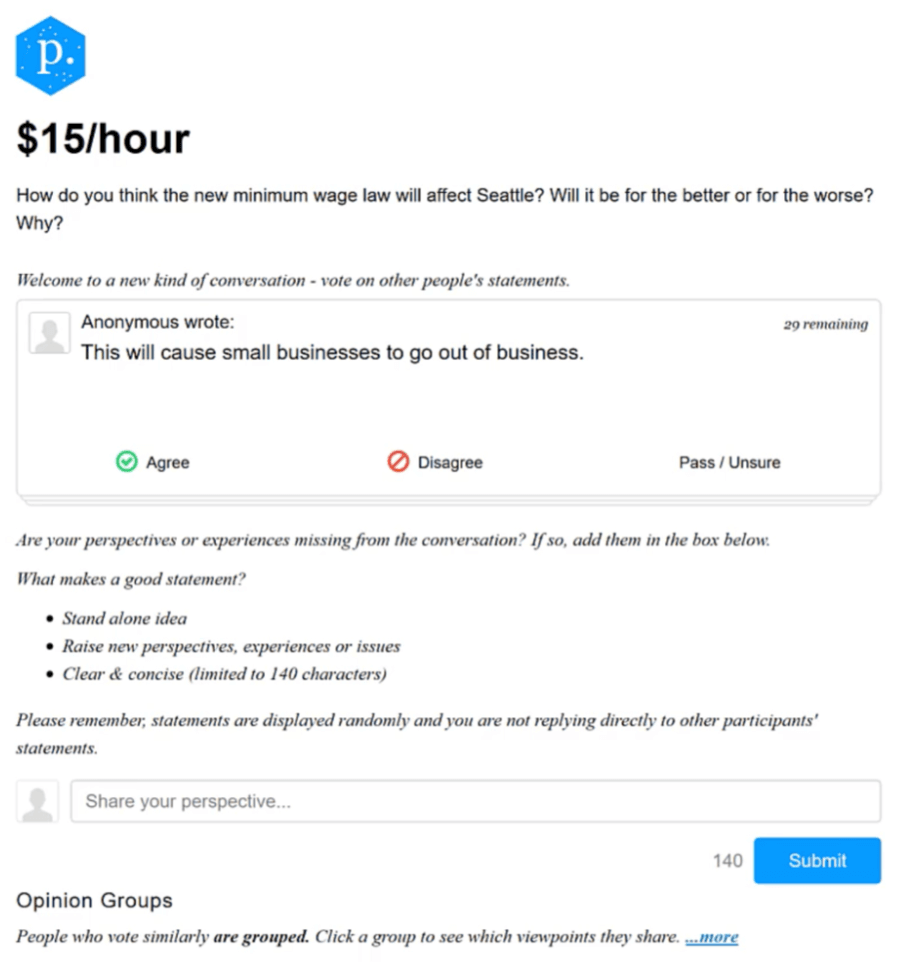

This doesn’t mean building new tools. There are off-the-shelf products that can do a lot of the groundwork. Here’s one example. Polis gets people to vote (agree / disagree / unsure) on statements that are made by other participants in response to a question. If your view isn’t represented you can add it when you’ve finished voting. It doesn’t use upvoting or allow you to comment in response to other people’s. It doesn’t let you throw your opinion out there without having taken other people’s views into consideration.

Polis uses AI to analyse the results. This way it can find majority views and look for opinion groupings within the participants. This helps surface people with similar standpoints and to look for patterns of shared opinion or bias. This could be used by grantmakers engaged in participatory grantmaking, to source feedback from large groups of people. It could also be used by small teams of grant managers to discuss and assess applications asynchronously and without messing around with spreadsheets or Word Docs. It’s more intelligent than a Google form and this increases with the number of people using it.

An open source autonomous micro-grant organisation

We wanted to push the idea of automation in a specific grantmaking context a bit further. Our aim was to really distill what machines helping humans do grantmaking could like. After some in depth user research with existing participatory grantmaking organisations. We prototyped an autonomous micro-grant organisation, where all of the admin is done by machine and the decision-making is done by humans.

As a provocation, this prototype does away with much of the work currently done by people working in grantmaking organisations. It automates some of it and leaves a lot of it to the donating community to decide.

This is not to say that the value of machines is in getting rid of people. It’s about freeing people up to get ourselves out of the bureaucracy and admin and do what we do best: make moral and ethical judgements about things, see nuance and draw on experience over time to better trust in our intuition and develop ways of knowing that might be called wisdom.

You can read about the research and try out the prototype for yourself.

Data for intelligence

We can’t think about collective intelligence without also thinking about data. Groups of people can both generate and interpret data. Advances in technology have broadened the pool of data with which we’re able to work, drawing on large sets of qualitative data as well as hard numbers.Data is helpful. It’s also really problematic.

For a start, there’s a lot of data out there. Community groups often don’t make the most of open data. Trafford Data Lab is an effort by the council to “support decision-makers in Trafford by revealing patterns in data through visualisations”.

But we should ask ourselves why this kind of digestible data visualisation isn’t more widely used. It’s probably not just because communities or grantmaking organisations don’t have the skills. Could it be that even amongst this wealth of data, there’s still something missing?

Towards the end of the second UK lockdown, Shannon Mattern gave a talk in which she asked “how do we map nothing?” She looked at the invisible networks that allowed some of the global population to spend months during the pandemic ‘doing nothing’. Doing nothing starts to reveal privilege and inequality. For example, while newspapers around the world talked about ‘the great pause’, ONS data shows that most people did not in fact work from home during the pandemic—only 26 percent of the UK population did.

“What if we took each sourdough starter, each Zoom class, each Peloton ride, each Netflix binge and mapped the ecology of resources and services that made it possible?”

– Shannon Mattern

Against the vacuum of quarantine, there were the Deliveroo workers, the healthcare workers, the civil servants, truck drivers, waste management employees all working day after day. Networks of maintenance and care are too often invisible. Mattern warns that data can obscure as much as it can reveal, by privileging that which is measurable over the intangible. She calls for a ‘collaborative cartography’ to surface these hidden networks. This would be an example of mobilising collective intelligence.

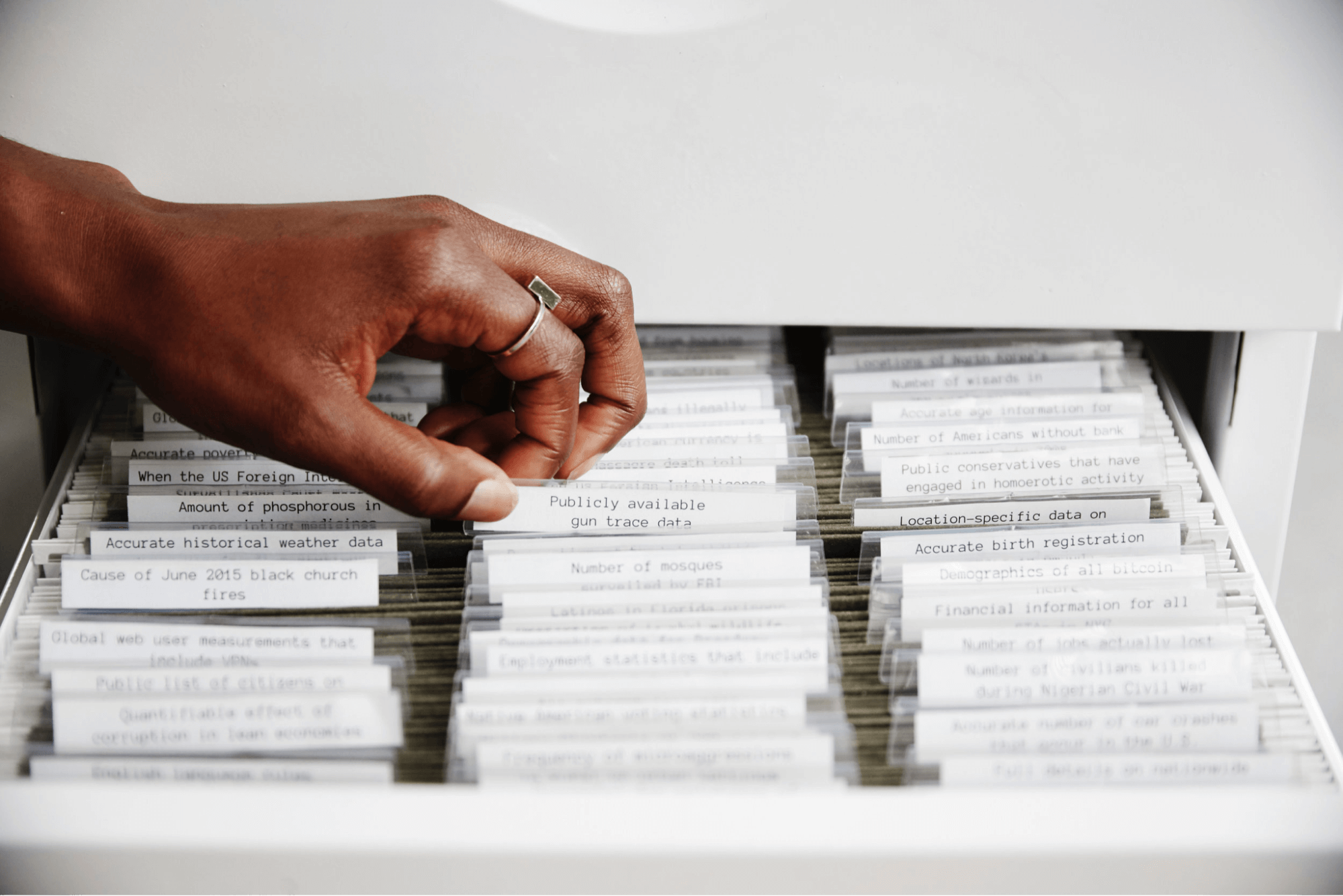

Despite the ever-growing number of open datasets, useful, useable data is not always readily available to those who need to use it. Artist Mimi Onuoha’s Library of Missing Datasets makes a powerful statement about notably missing datasets in the US, such as publicly available gun data.

Image: https://mimionuoha.com/the-library-of-missing-datasets

Data is biased. It’s created by human beings and like human beings, comes from a situated place and people whose views of the world are partial. Poorly structured, or ‘messy’ data, often goes through a process of ‘cleaning’ to smooth out disruptive or non-conforming information. This act of standardisation can obscure or erase other types of meaning that data might have offered.

“In the perceived messiness of data, there is actually rich information about the circumstances under which it was collected.”

– D’Ignazio and Klein (2020)

Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein’s Data Feminism offers a comprehensive and detailed critique of unconsidered uses of data (2020). While being champions of the value of data and data science, they examine the ways in which rather than being a reductive, opaque science, data can support and enrich our understanding of the world through plurality, embodiment, emotion, context and transparency.

It’s important to stress that we’re not only concerned with numerical data. Collective intelligence (and machine intelligence) opens opportunities to use different kinds of data and starts to dissolve the unhelpful binary between quantitative and qualitative data. ‘Big qual’ is the practice of analysing large sets of qualitative data. Warm data is the practice of looking at the relationships between many moving data points in one or more complex systems. Both rely on, or are enhanced by, collective interpretations or contributions as well as machine intelligence.

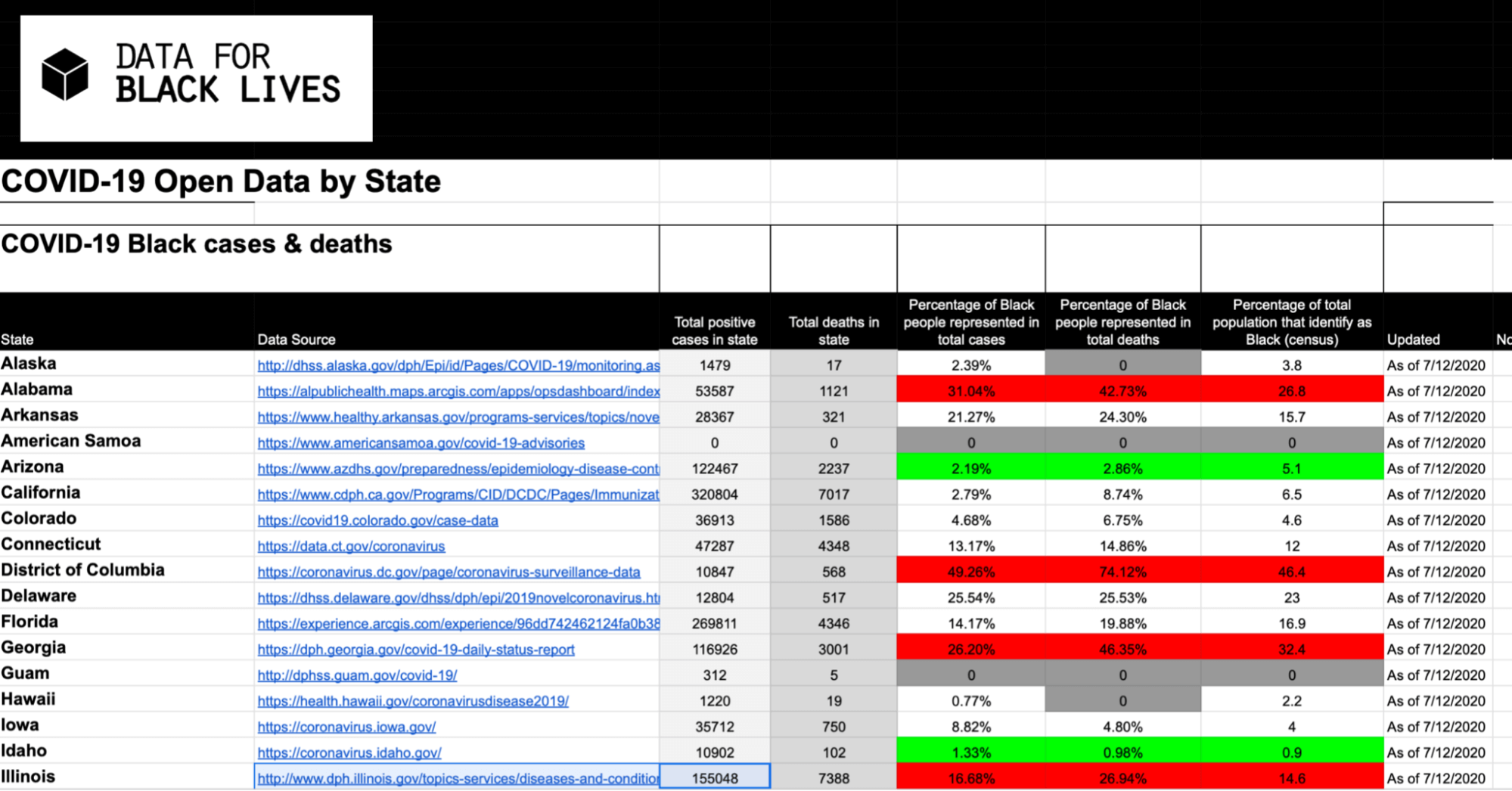

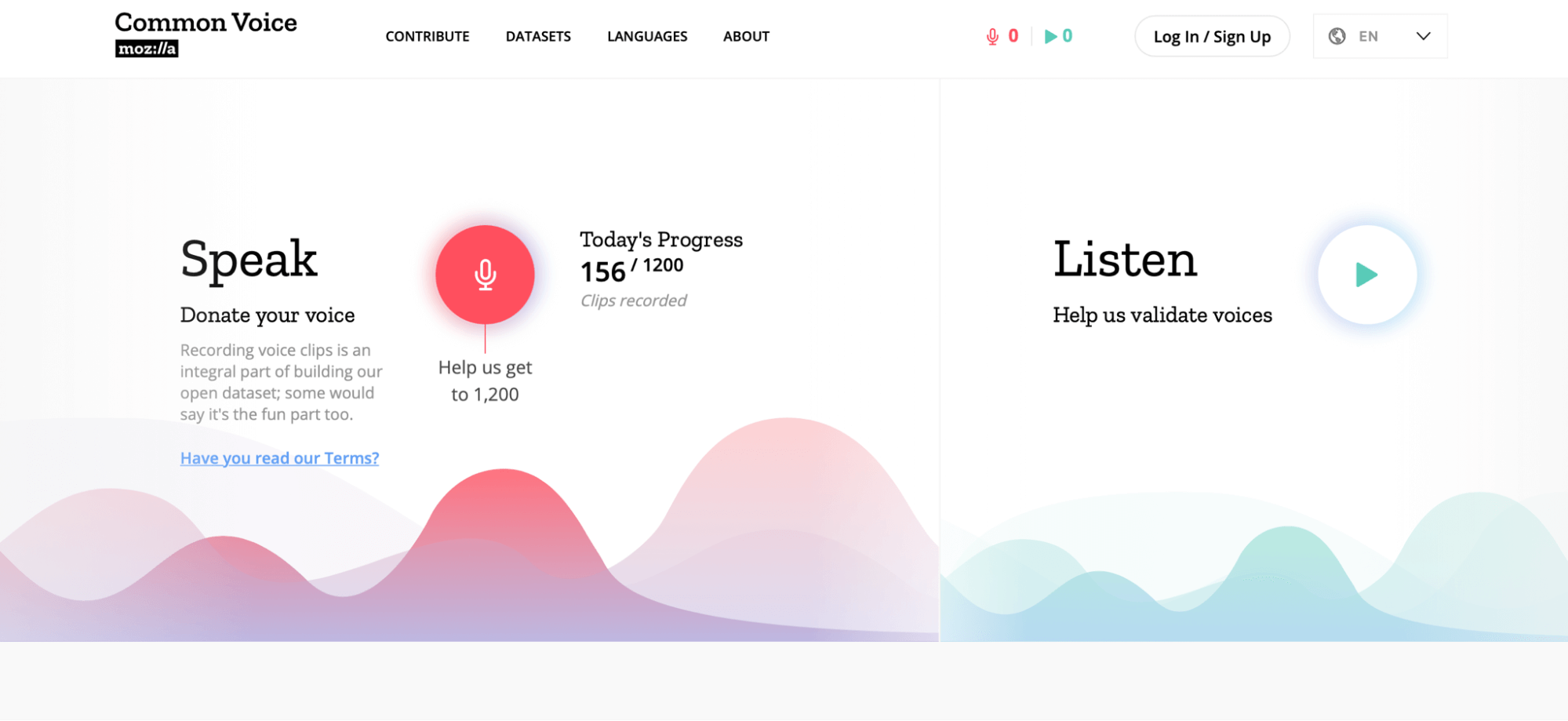

Image: https://d4bl.org

Data for Black Lives and Design as Protest are collective efforts in addressing such gaps in data. Mozilla’s Common Voice is a crowdsourced open dataset of people’s voices, so that we don’t all have to sound like Californian tech bros to use voice as interface. All of these are examples of mobilising collective intelligence—the power of people plus technology—to begin plugging the gaps in datasets, improving representation and surfacing neglected stories.

Image: https://commonvoice.mozilla.org/en

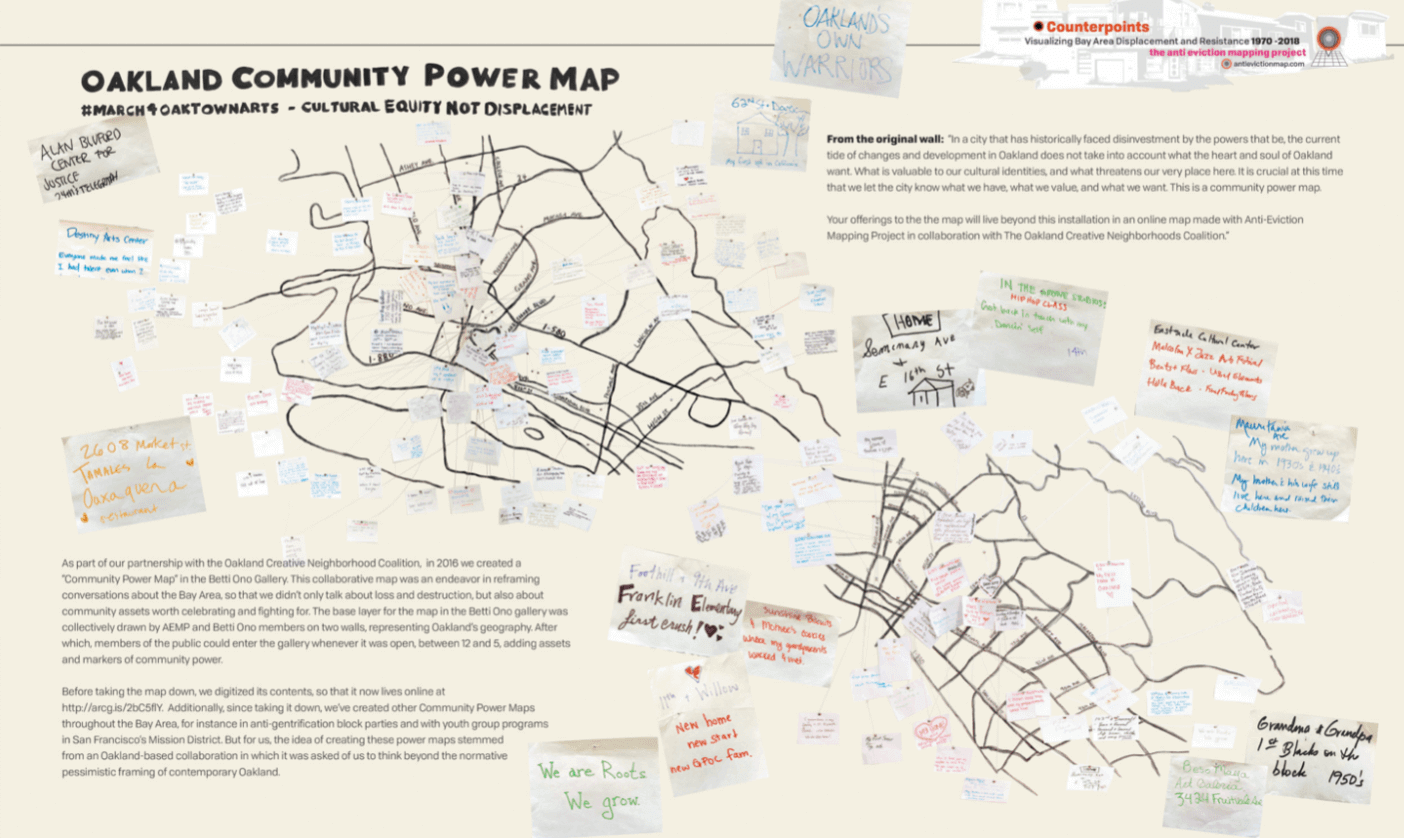

The 2013 Anti Eviction Mapping Project started in San Francisco to map and resist displacement through gentrification. People in Oakland came together to map their stories and histories of the neighbourhood. This messy, feral mapping told a different story to that which came through real estate data. It captured people’s memories, hopes and dreams, challenging on one side, a story of success and progress and, on the other, a story of poverty and exclusion. Instead, it tells stories of rootedness and love, of family and survival.

Image: https://antievictionmap.com/oakland-community-3

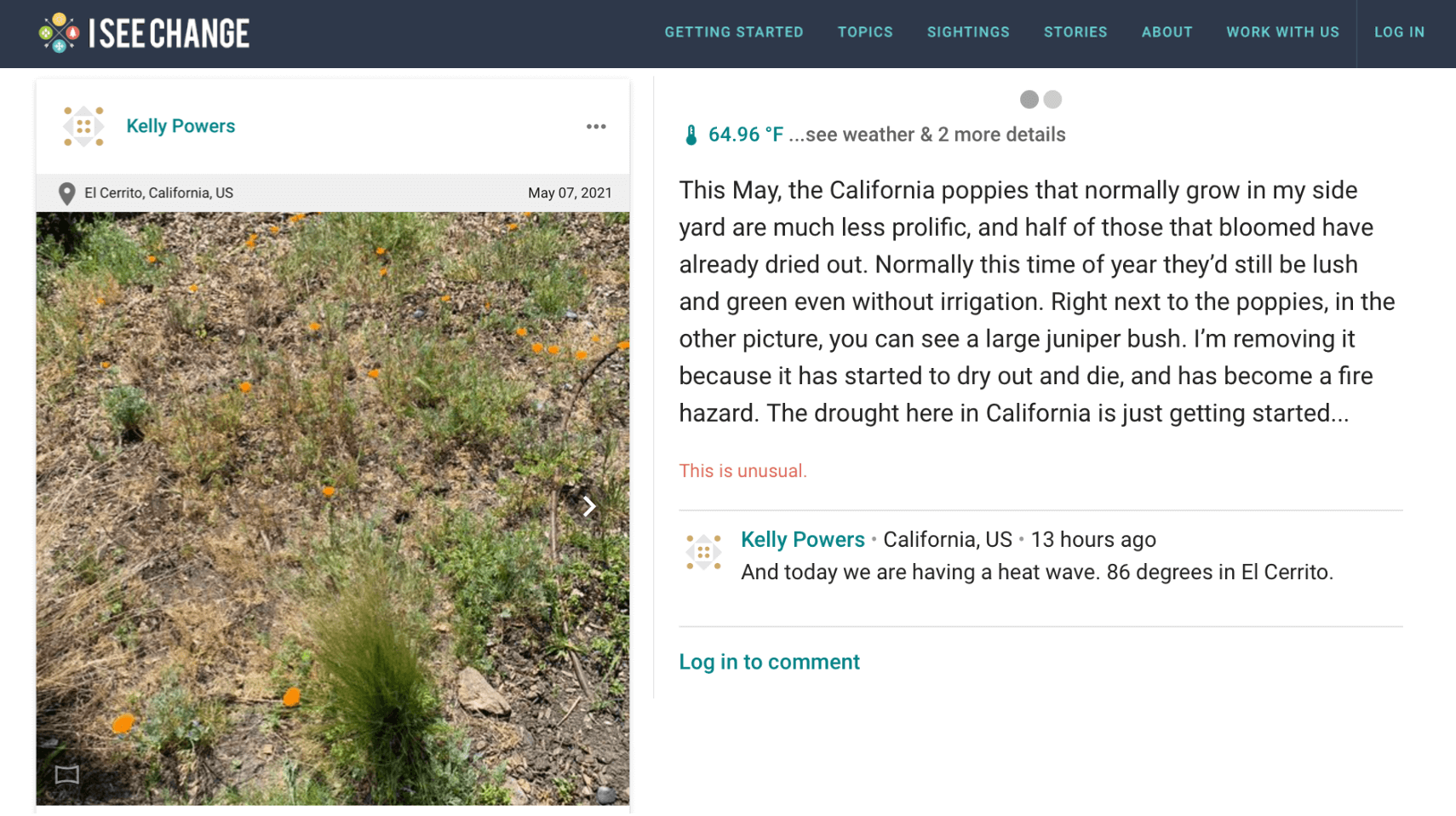

Technology can help make sense of large amounts of this kind of rich, qualitative data. I See Change asks people to gather quantitative data (like temperature), photographs and free text to document the natural environment. It draws on people’s experience and knowledge of an area to aggregate rich data on climate change. The free text provides space for contributors to reflect on what the situation was like last year, five years ago or even when they were a child.

Image: https://www.iseechange.org

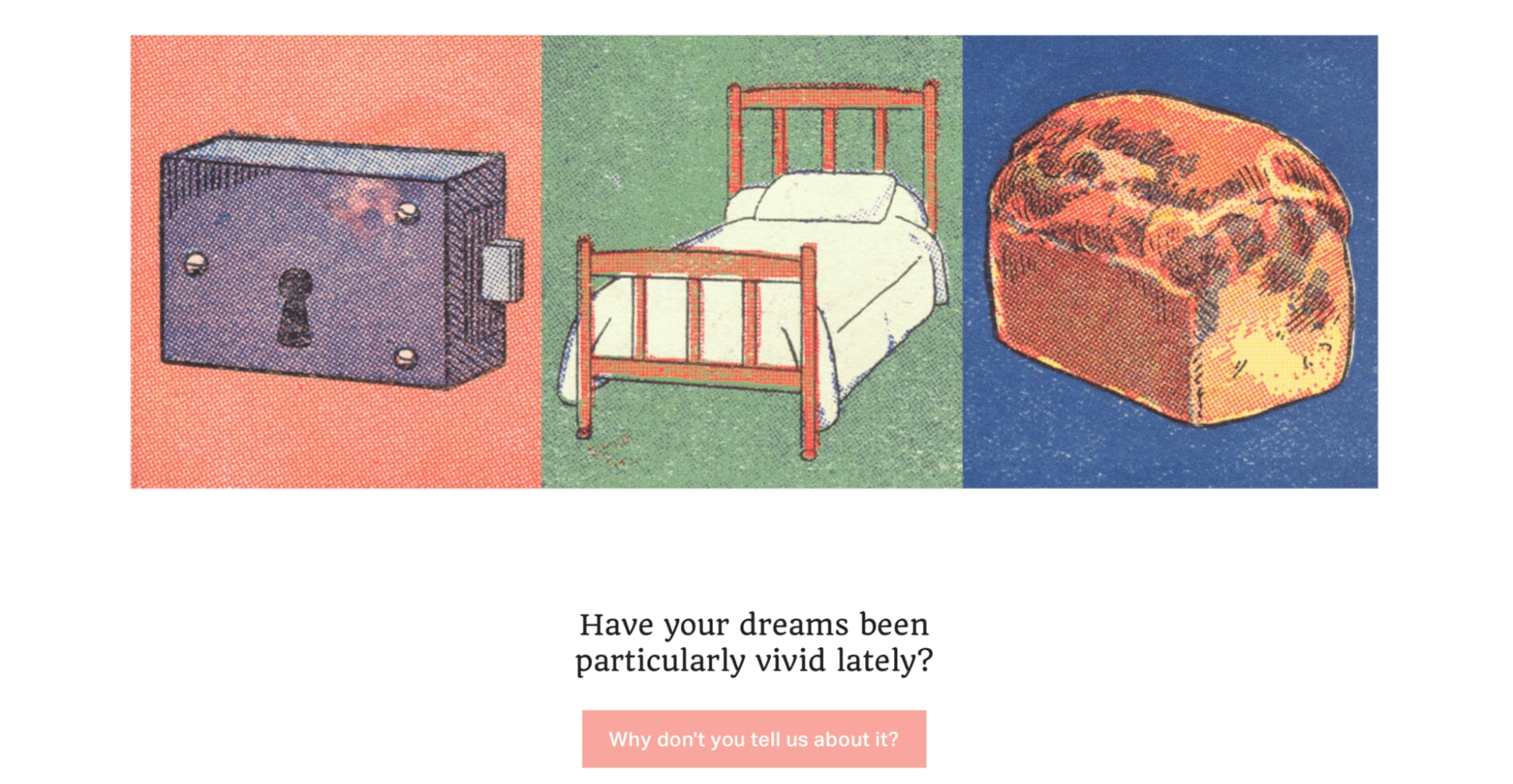

During 2020, UCL gathered unstructured data on people’s pandemic dreams through a web form. Similar experiments were carried out by universities in Finland and the US. These used software to analyse and cluster words and sentiment and look for patterns.

Their early research starts to tell stories about a collective mood during the pandemic, with different themes appearing in different countries. This builds on our understanding of the pandemic by going beyond numerical data of infection rates or deaths, and telling a story of what it was like to live through that event by capturing the impact on our collective psyche.

People can also help interpret data by working collectively. In one of the most exciting examples of collective intelligence being put to use for social good, Amnesty International’s Decode Darfur engaged volunteers to look for evidence of attacks on settlements in Darfur using satellite images. In the past, this would have been done by eye-witness reports, a slow and dangerous activity. Different from direct experience, the Decoders work is what Jonathan Gray has called ‘data witnessing’ and involves human and non-human actors analysing violence asynchronisly and at a distance (2019). This is a great example of how a live conflict situation can be critically analysed very quickly with large, dispersed groups of people pooling their collective intelligence.

Image: https://decoders.amnesty.org/projects/decode-darfur

Data in grantmaking

The growing wealth of data grantmakers have access to is great - who doesn’t like to have a nice, clean number by which to judge whether something is working or not?

But data abundance can also be a trap. The simple fact that some data exists can be the driving factor in making us use it. How often do we stop to ask, is this the right data? Is this the best way to measure this? Or, what might be missing from this data? When solving complex problems, single data points can only ever be a proxy for what’s happening. This means that what’s measured isn’t always what’s really important. When you’re faced with a spreadsheet of outcomes data, this can be easy to forget.

Outcomes data is probably the most prominent form of data in funded projects. It’s used to measure success (in the form of targets) and as a proxy for impact (when reporting back). Although many grantmaking organisations are vocal champions of lived experience, working hard to involve people with lived experience in their funding and to make sure their voices are heard, we still look to numerical “hard” data as incontrovertible evidence of whether progress is being made.

Fixating on the data can reduce complex problems to a single data point, offering the illusion that shifting that data in one direction or another is the same as solving the problem. This is rarely the case. Planting more trees, for example, does not automatically equate to cleaner air in cities. The benefit a tree has on the environment increases as it matures, over a period of 150 years (when it starts to drop again). If mature trees are lost during that same time period, the measure of tree planting has little benefit.

Writing about the idea of non-white women “finding a voice,” bell hooks warned against privileging “acts of speaking over the content of speech”. That is to say, giving someone a platform is not the same as engaging with the message they are sharing (hooks, 1989 p.14). Privileging presence over perspective, reduces the act and the actor to a “commodity, spectacle” (Nadar 2014 and ibid.). Perhaps it’s useful to apply this idea to outcomes data. There is a risk that in focusing on the representation of quantifiable outcomes data alone, funders can miss the messages held within that data. In doing so, they reduce potentially transformative social outcomes, to a number. Taking a cynical eye, we could say that outcomes data becomes a commodity that funders buy when they fund a project.

There also seems to be something of a false binary within grantmaking, where “hard” data on the one hand is set up in opposition to “anecdotal” lived experience on the other. Some grantmakers, or approaches to grantmaking, tend to privilege one over the other. We should ask how participatory grantmaking, for example, can make better use of data as a way to strengthen rather than challenge people’s lived experience. We should also ask how funders that are doggedly data-driven can broaden their definition of data so that it retains nuance and reveals a more complete picture.

In breaking down the data/lived experience binary, there is a significant opportunity in collective intelligence for grantmakers to involve the communities they work with in gathering data that paints a fuller picture and makes space for alternative narratives. This could be all kinds of data, numbers, pictures, audio and text. Doing this as a collective process has the benefit of supporting communities to develop and strengthen their own narratives as well as developing the knowledge of the funder. It would be a radical act for funders to look at data not just from the point of view of ensuring project delivery, but what data can provide in terms of ongoing learning and adaptation, shared dreams and long-term aims. This should be designed with the communities they’re supporting as a more fluid and plural approach to data insight that holds a greater collective value than the dominant technocratic view of measuring progress.

As the previous examples show, collective intelligence encourages us to work with data that is rich and textured, reflecting the complexity of the world. It opens opportunities to dissolve the unhelpful binary between quantitative and qualitative data where ‘hard’ data on the one hand is set up in opposition to ‘anecdotal’ lived experience on the other. In breaking down the data/lived experience binary, there is a significant opportunity for grantmakers to involve the communities they work with in gathering data that paints a fuller picture and makes space for alternative narratives. This could be all kinds of data, numbers, pictures, audio and text. Doing this as a collective process has the benefit of supporting communities to develop and strengthen their own narratives as well as developing the knowledge of the funder. This way of working promotes data as a collective good, rather than a yardstick against which grantmakers hold grantees to account. It would be a radical act for funders to look at data not just from the point of view of ensuring project delivery, but what data can provide in terms of ongoing learning and adaptation, shared dreams and long-term aims.

4. What other kinds of ‘intelligences’ or ways of knowing or intuiting could communities draw on when imagining, decision-making and deliberating?

From Intelligence to Intelligences

Intelligence is a slippery concept and one that is too often taken to mean what Patricia Hill Collins refers to as ‘book smart’—learnt intelligence that comes from the privileged and distant activities of theorising and thinking (2009). Whether we like it or not, many grantmakers tend to privilege this expertise at the expense of other ways of knowing, reducing intelligence to a narrow set of skills, experiences and world views. This removes agency from those who do not share such experience or interpret the world in the same way but who are, nonetheless, critical players in implementing change. When it comes to solving complex, dynamic social problems, we need a broad definition of intelligence because the true power of collective intelligence lies not just in aggregating discrete viewpoints but in how people with radically different viewpoints can work together over time.

This interpretation echoes the idea articulated by Donna Haraway that every view of a situation is formed by where the viewholder is standing (1988). If all knowledge is situated and partial—that is, it is constructed by a person whose experiences cause them to approach an issue in a certain way—then one person alone can only hold part of the picture of any given situation. This is why participatory grantmaking that encourages representation from a small number of people with unique lived experience can only ever go so far. Many people together, with diverse experiences, can build a more complete picture of that situation and discover more effective ways to solve problems. This is pertinent particularly when taking a systems approach to social problems and the myriad causes and influences that feed into issues like poverty or domestic violence.

“We seek those ruled by partial sight and limited voice - not partiality for its own sake but, rather, for the sake of the connections and unexpected openings situated knowledges make possible. Situated knowledges are about communities, not about isolated individuals. The only way to find a larger vision is to be somewhere in particular.”

– Donna Haraway (1988) Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective

Of course, having a different opinion on a subject is not the same as having a fundamentally different world-view of a subject. How can collective intelligence combine different kinds of knowing that result in different understandings or framings of a situation? This means combining ways of knowing that come from learned, lived and practice-based experience. It can include intelligence from ancient philosophies and the natural world. It welcomes neurodiversity and involves people who can imagine as well as those who can analyse. Bringing together these different ways of knowing on an equal and collaborative footing expands our understanding of a problem and has greater potential for impactful collective action.

By exploring different intelligences that stem from diverse ways of understanding the world, philanthropic organisations can begin to free themselves from the limits of their current practices and imagine transformational models of working that are more integrated into the communities they support and better serve their ambitions. Here, we outline just four examples of ways of knowing that are relevant to contemporary issues—embodied, imaginative, decolonising and ecological intelligence.

Embodied intelligence

Thinkers such as Haraway, Patricia Hill Collins and Francisco Varela argue that intelligence is situational, embodied and relational. That is to say, if we are intelligent in our minds, our minds are inherently part of our bodies. It is through our bodies that we experience life, ideas, situations. To be educated about a situation is one thing. To have lived in that situation, to have reacted to it and felt the consequences of your actions, is quite another and brings with it a different level of understanding. Dance and physical theater are used as mediums to address trauma—with people in prison, for example—precisely because they connect the mind and body in ways we are often discouraged from exploring in everyday life.

“The world is not something that is given to us but something we engage in by moving, touching breathing, eating.”

– Francisco Varela (1999) Ethical Know-How: Action, Wisdom and Cognition

We accumulate our environments and experiences, and perhaps, those that are passed on to us through generational or community histories, within our minds and bodies. These can be valuable sources of intelligence and wisdom if we allow ourselves to listen to them effectively.

I wonder if we should replace the term “lived experience” with “lived expertise”

— Thea Snow (@theasnow) May 24, 2021

While many grantmaking organisations have long been champions of lived experience, they’ve not always had the tools or skills to be able to make the most of the insights and expertise it provides. Funders are constantly trying and struggling to integrate ‘the voice’ of lived experience into their processes. But lived experience deserves more than just a voice. Equity of contribution matters. Collective intelligence can support this by building on existing participatory grantmaking and diversity outreach efforts, elevating the status of lived experience by giving it weight through volume and data and by using technology to engage more people with lived experience in the discussion, decision-making and delivery of grants.

Imaginative intelligence

It would be hard to change the world without being able to imagine what a different world could look like. In his 2020 paper The Imaginary Crisis, Geoff Mulgan argues we need social imagination to help find a way through crises like global inequality and climate breakdown. Against this backdrop of warnings about the crisis in social imagination, there are organisations, institutions and people working to develop tools and spaces to rekindle public imagination.

Helping communities to bring about fundamental change means helping them to radically imagine different worlds. We can only address complex societal problems as a collective, so we need to imagine as a collective. Work such as the Emerging Futures Fund has propelled this kind of dreaming forward. Related projects such as Imagination Infratstructuring and their Collective Imagination playbook provide resources, practical approaches and examples for how to reignite public imagination. This kind of work focuses on growing skills around wayfinding, sensemaking, worldbuilding, speculating and narrative infrastructure. It takes responsibility for imagining out of the elite discipline of future studies and the hands of single authors, to re-embed our capacity to design better futures within communities.

Alongside lived experience and analytical expertise, the capacity to imagine is critical if we are to reconstruct the world as a better place. Social imagination serves not only to orient towards preferable futures, but as an important reminder that it is we who construct the world we live in today and we have the capacity to reconstruct it.

Decolonising intelligence

There are a wealth of neglected or marginalised philosophies currently experiencing the interest they deserve as part of efforts to decolonise social thinking. See, for example, Arturo Escobar’s Design for the Pluriverse (2018), Tyson Yunkaporta’s Sand Talk (2020) and Camae Ayewa and Rasheedah Phillips’ concept of ‘Black quantum futurism’, as well as organisations like Whose Knowledge? which actively works to bring the knowledge of the marginalised majority to the fore. These are philosophies, practices, and ways of living and thinking that have complex and deep histories: it would be futile and inappropriate to even attempt to summarise them here. The important takeaway is that there are rich alternative models of conceiving of and engaging with the world that have been marginalised, neglected or appropriated, without the depth of understanding they require. Grantmaking organisations working with specific communities or in particular geographies should do the work to understand the different modes of thinking and value systems that may exist and engage the people who steward that knowledge.

The collective behind Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures provide resources on pedagogical, artistic and cartographic experiments, as well as frameworks and principles for engaging in community-based work that actively seeks to decolonise existing practices. This involves tackling racism, colonialism, heteropatriarchy and nationalism. Much of the practice is about hospicing, composting and facing complicity in violent practices. It is also about recognising our entanglements with the wider living world and the limited resources of the planet.

Image: https://decolonialfutures.net/mapping-decolonization/

Philanthropic organisations need to recognise the weight and wisdom of ingenious intelligences, particularly when those ways of relating to the world have been marginalised or erased. This kind of thinking can help grantmakers recognise their own exploitative practices and offer paths to let them go. It can also help grantmakers work more consciously with communities suffering the violence of such practices.

Ecological intelligence

Ecological intelligence offers an inherently collaborative framing of the world. It looks at the interplay not just within systems but between different systems, micro (eg. at a cellular level) and macro (eg. between ‘individual’ actors). By privileging connectedness, the exercise in thinking as an ecosystem can help us see and better value links between the human and more-than-human, and the impact of actions in one place, on another thousands of miles away. It takes inspiration from the mycelial networks that transfer nutrients and information across forest root systems and the occurrence of inosculation—when the branches or trunks of different trees rub and fuse together, supporting and feeding one another as a new hybrid organism. It is inherently cyclical, rejecting the forward notion of time for one that is seasonal and pays attention to composting old ideas in order to fertilise new ones.

This is called inosculation: when branches or roots of different trees are in prolonged intimate contact, they often abrade each other, exposing their inner tissues, which may eventually fuse.

— Ferris Jabr (@ferrisjabr) May 21, 2021

It's not so much one tree feeding another as the formation of a new hybrid organism. https://t.co/gvXZlkEhDd

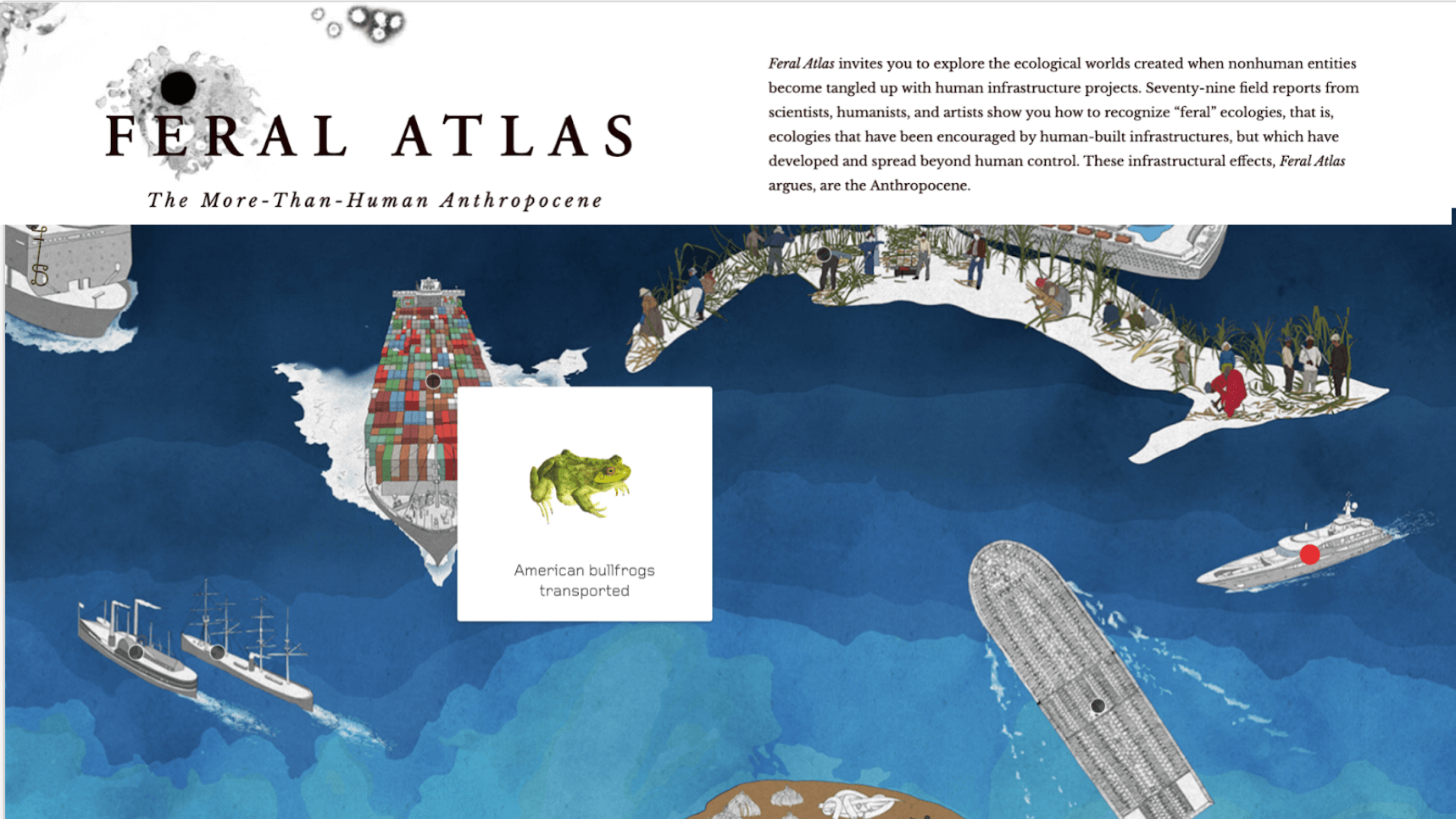

The Feral Atlas, made by Anna Tsing and colleagues, explores entanglements between the non-human, more-than-human and human infrastructures, offering a messy, revealing picture of lives in the anthropocene. This is not an atlas like any you’ve known before. It crosses space and time, placing slave ships alongside contemporary cargo, to remind us of the deep historical legacies and present day realities of past actions.

Image: https://feralatlas.org

In the context of grantmaking, ecological thinking should cause us to proceed with caution where any single project or solution promises a fix. It points instead to recognising the myriad interdependencies that arise across diverse funding portfolios—systems and ecosystems thinking. It should encourage grantmakers to embrace cyclical learning and the composting of old work to fertilise the new.

Collective intelligences

Where, then, do these intelligences come together? In her article and subsequent book, Fathoms, Rebecca Giggs describes the experience of watching a whale repeatedly beach itself on the sand in Western Australia (2020). It was, in her words, “a public attraction” with people cheering on, taking photos of and, ultimately, standing vigil over the dying creature. What do those witnesses learn from the sight and smell of a dying mammal? What did they learn from the physical act of trying to guide a whale back out to sea? How might this shape their views and understanding of nature or climate change?

“Guts are political. Not only can we learn from bodies, corpses, intuition, emotions and feelings, but we are affectively and viscerally touched by policies, whether we know it or not.”

– Sarah Marie Wiebe (2020) Sensing policy: engaging affected communities at the intersections of environmental justice and decolonial futures

Like the rest of us, whales consume their environment. Giggs details the amount of plastic and chemicals that accumulate in a whale’s body. The scale and longevity of whales means these build up in staggering quantities, making the whale even more toxic than the environment it’s in, so much so that the Canadian government disposes of beached whales as toxic waste.

“I thought of the humpback in the dump. The whale as landfill. It was a metaphor, and then it wasn’t.”

– Rebecca Giggs (2015) Whale Fall

The whale here is a site where embodied intelligence meets ecological intelligence, leading to a deeper understanding of the situation and ultimately how we view the world. In other whale strandings, decolonising intelligence has also come into play due to the special significance whales have to some indigenous communities. They all come up against analytical intelligence in the form of the legal policies that govern the disposal of the whale. Can we get better at harnessing the learnings that come from these different ways of knowing? What would it mean to engage the insights gained from embodied, ecological or decolonising intelligences in discussion so that communities and governments might start to tackle the root causes of the strandings in the first place?

Image: CTV News

Resilience Dialogues is a step towards doing just this. The dialogues facilitate online discussions between community leaders, scientists and practitioners to look at risks presented by climate change and extreme weather. Through the dialogue they aim to build shared commitment to future action. The key, of course, is how well each of these discussions work—whether equitable space and time is given to the different intelligences that each participant brings.

In lab experiments carried out by the MIT Centre for Collective Intelligence, Anita Woolley and colleagues demonstrated that groups that are socially sensitive, diverse and without hierarchy are more capable of solving problems. In highly intelligent groups, members were acutely aware of other members’ inputs with everyone making more or less equal contributions. The individual intelligence of group members had no bearing on how successfully they completed the task. How a group works together is the single most important factor in well-functioning groups, more so even than the intelligence of any individual in that group. The challenge is how we encourage this kind of behaviour outside the lab and in the real world.

Collective sense-making or enactive cognition is the idea that we make sense of the world and ourselves by engaging with it and other people. Two people sharing knowledge creates new knowledge that neither person could have known alone. If intelligence is formed by our relationships with other people, how we engage in those relationships matters. Working together can be hard, especially when people don’t just hold different views, but conceive of the world in fundamentally different ways. Grantmakers working with communities have to start to ask, how can a group hold multiple worldviews? What might that look like?

“When we reject the single story, when we realise there is never a single story about any place, we regain a kind of paradise”

We can take inspiration from the Zapatista concept of ‘un mundo donde quepan muchos mundos / a world where many worlds fit’. This means striving for multiple points of view and ways to frame our worlds. Our situated partial knowledge is not a bad thing. Rather, it’s good as it pushes us towards collaboration with others.

In embracing collective intelligence, grantmakers need to focus more attention on the relationships and behaviours of the groups they fund. When writing about the importance of dialogue in coming to know something, Hill Collins draws on African American call-and-response heritage. This isn’t the combative, distanced reasoning of Enlightenment thought. It’s an exercise in building one idea on top of another. Less the single truth captured in a WordDoc and more the duet function of TikTok. How do we learn to harmonise while all retaining our original contribution? What could funders do to encourage the acceptance of different standpoints within groups? How can they help groups to disagree comfortably? This could be a better indicator of the success of a project than having a team with deep but singular expertise or a promising looking project plan.

5. If ‘collective intelligence’ was to grow into ‘collective wisdom’ how might that be developed during a grantmaking process?

“The difference between collective intelligence and collective wisdom is probably the benefit of hindsight,” says Nesta’s Kathy Peach. “You can look back on a course of action with an understanding of context and impact that weren’t available to you in the moment.”

Cassie Robinson, who commissioned this work, has a similar view. “Wisdom, for me, comes from having courage, taking risks, learning and gaining the experience that allows you to trust and develop your intuition in new contexts,” says Cassie. “As grantmakers we should support grantees and communities to draw on past experiences to help them anticipate future problems as well as tackle the ones we’re experiencing right now.”

Collective wisdom then, is not focused on solving the problem per se, but rather developing a relationship with that problem that can evolve and adapt as the nature of the problem changes. What Cassie describes requires more than sustained financial investment on the part of philanthropists. It asks grantmaking organisations to play a role in stewarding communities to work as diverse groups of people who not only hold different viewpoints, but different world views. It is long, deep work with fundamental implications for the way philanthropic organisations are staffed and work, demanding longer timeframes, a different starting point, comfort to work with uncertainty, richer ways of measuring outcomes and very different skills and responsibilities for employees.

To move towards collective wisdom there are six practical steps that grantmakers could try. Taken together, they form the foundations for reconceiving of grantmaking organisations less as responsible distributors of funding and more as investors in community infrastructure; mobilising collective intelligence and working from an abundance mindset. This means reorienting focus towards creating the conditions that allow for the surfacing of plurality and difference, and turning difference into a strength.

Abundance Grantmaking

1. Automate repeatable tasks and let humans do the hard stuff

Nobody wants to be drowning in Google Docs, or spreadsheets or diary invites. Automation offers the opportunity free people from routine tasks. Tools similar to Applied could help remove a level of bias from the grant application process. Then you can start to ask, how might our time be better used to achieve our goals? What are the things only humans can do? These are things that might involve relationships, moral and ethical judgements, subjectivity. What new skills do we need in the organisation around data science and data ethics, coaching and behavioural science? How do we encourage those working in grantmaking to develop their intuitive knowing - what have they learned over time, what kind of knowledge has deepened, how has their positionality with a view of the field shifted their knowing? And how can they combine their intuition with other kinds of data? How do we recognise this as wisdom?

2. Fund community groups, not projects

Given that research from across the spectrum shows that the diversity and collaborative behaviours of groups is what determines their success, why do we spend so much energy focusing on projects and programmes? Grantee teams need to be socially sensitive, diverse, equitable and comfortable with pluralistic world views. Instead of pouring over project proposals, funders should consider how to support productive and generative group dynamics among the people they fund.

This means investing more than just money. There are many grantmakers that fund people directly and others that have experimented with direct devolution of funding to communities. The big question is about how intentionally and effectively it gets done. What if a funder’s largest contribution was in time spent coaching and working with community groups on how they work together? This could include helping them build coalitions of support across different sectors. It might mean spending significant time developing relationships with lawyers, local government or other institutions. Yes, this is systems thinking, but it’s also systems building—creating the relational infrastructure—that governs how communities work together.

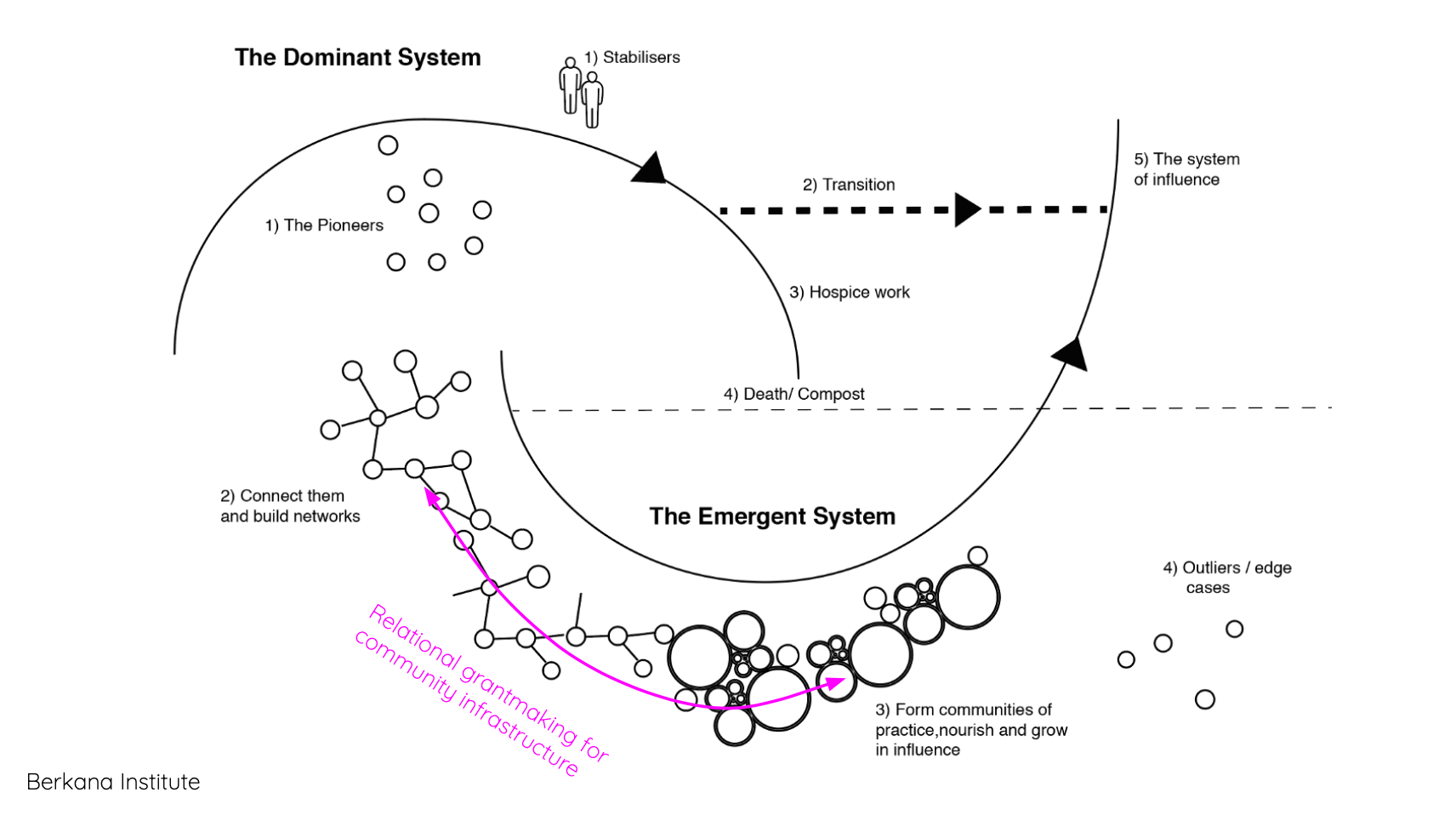

Focusing on groups rather than projects also opens space for learning; cyclical learning that is free from a restrictive, linear conception of progress. This is the hard work of connecting pioneers with different experiences and outlooks, and helping them to form new communities of practice, intent, action and influence.

Image: Berkana institute

This is the hard work of connecting pioneers with different experiences and outlooks and helping them to form new communities of practice, intent and influence.

3. Become experts in group behaviour and group potential, harnessing a range of intelligences to support communities to work together

To support grantee relationships effectively, the skills of staff within philanthropic organisations need to look quite different. They become experts in behavioural dynamics, coaching and stewardship to help grantees draw on a range of intelligences to understand problems and inform approaches. The grant manager’s role would be to cultivate a diversity of intelligences and tend the relationships in grantee communities rather than assessing the quality of a project plan or application form. This is a stark change for organisations that are structured around the responsible allocation of money.

Nesta’s How to Make Good Group Decisions is one place to start. Guiding community groups on a journey requires confidence and experience. It will require a significant investment in skills and people from any grantmaking organisation wanting to take this up. The Behavioural Insights Team’s Behavioural Government report identified the heuristics and biases prevalent among government officials and designed ways to address them. What might be the systemic patterns and behaviours we find in community groups working with grantmakers? How might we work to change those?

Growing a whole new field of professional expertise within a sector is no small task. But it also opens up the opportunity for funders to diversify their workforces by recruiting and training employees themselves, allowing them to bypass the structural biases in existing routes into philanthropy and actively recruit from underrepresented communities.

Without running headlong into the metaverse, this could be done with a combination of in-person and online environments. The increase in remote working has seen technologists scramble to create online spaces that reflect, complement and in some ways, enhance in-person work. Mozilla Hubs and Gather are two examples of this They’re far from perfect, but they do offer ways of thinking about collaboration beyond physical proximity. The Institute for Technology in the Public Interest compiled a list of formats with examples of creative online spaces that can help us get beyond the ‘zoomification’ of all digital interactions. As one student at Nottingham University told The Guardian. “Joining in as an avatar gives you a veil of anonymity that has made everyone less awkward about speaking up in class. In some ways, I feel more present than if I was physically there.”

What other tools might help us engage with other intelligences? These are ones that can help us track or confront our own responses, ideas and feelings so that we go into situations with a greater level of self-awareness and can better accommodate others.

4. Start working with groups at the scoping of possibility and problem definition stage, not solution stage

Funders should help communities to build, see and embrace the messy picture of their world that comes from multiple viewpoints and support them to accommodate difference from the start. Working through the different ways to approach a social issue can be a foundational bonding experience for grantees, giving them the chance to develop their understanding with each other.

When a project proposal is submitted, it’s already too late. Funding application forms demand a single framing of the problem and discourages learning from risk taking. What’s more, as a grantmaker, you may hold a different understanding of such a problem and reject promising activity as a result.

Rather than asking what the solution is, philanthropists should work with a community to better understand the problem and the full breadth of possibilities for change. The funder’s role is to challenge them to explore alternative narratives. That way they benefit through deeper understanding of their own contexts too.

“The research we do is not solely for the sake of theory building but for the sake of community building”

– Sarojini Nadar (2014)

5. Collect diverse forms of data, and analyse it in novel ways and take care of it.

There are huge opportunities for funders to be more innovative in the way they use data, moving beyond dogmatic outcome measures and towards using richer sources generated and interpreted with the help of technology or grantees themselves.

Funders can help dismantle the unhelpful binaries between quantitative and qualitative data, and be open to listening to new insights and ways to think about the world. Data work such as feral cartography can be collaborative exercises that help forge deeper understandings and relationships. Progressive grantmakers will see the value of data in terms of what can be learned, and what can become possible, rather than simply what can be assessed.

This means investing in lots of good data science capability: data scientists who can deal with big qual as well as the numbers and those who are familiar with the pitfalls of data, who understand that their role is as a guide and steward, not a manipulator or special reader of data (D’Ignazio & Klein, 2020).

6. Tear up your funding application forms

If the previous suggestions are adopted, the current model of applying for different funds is obsolete. There’s no point in proposing a solution if the funder wants to start at the scoping stage. There’s no need to focus on a project plan if it’s the people executing that plan who matter. Philanthropic organisations have the opportunity to completely redesign the application process so that it focuses on the people doing the work, remove bias from the process or draw on a large pool of people to help with the selection process.

This probably means stepping away from word processed documents or online forms. ‘Collaborative tools’ like Google Docs still insist on the dominance of a single narrative and work best when written, or at least edited by, a single author. When a sentence is edited it’s hard to see, unless you’re happy (and able) to trawl through different version histories.

Image: TikTok

What if we thought about it more as TikTok’s duet function? When talking about the importance of dialogue in coming to know something, Patricia Hill Collins draws on African American call-and-response heritage (2000 p.279-281). This isn’t the combative, distanced reasoning of ‘rational’ enlightened thought. It’s an exercise in building one idea on top of another. How do we learn to harmonise while retaining our original contribution?

Funding decisions could instead mean a more active recruitment of networks of people who bring an entanglement of lived, learned and practice-based experience. It would mobilise behavioural expertise among grant managers to focus on the diversity of experience and collaborative relationships of a group.

Working abundantly

Collective intelligence offers grantmakers the opportunity to make a step-change in the way they work, making all philanthropic funding inherently participatory. It’s not a change that will be easy or quick. It involves reevaluating the role of data, embracing the power of different intelligences and understanding what working together as a collective means. Collective wisdom asks funders to bring depth, breadth and plurality, and assign value differently. It challenges dominant narratives, helping us to see the world differently and showing that the collective can come to know things that an individual alone never could. It can help us to develop new ways of thinking and taking action together, not solving a problem but developing a relationship with that problem that will enable a sustained systems approach. It can redefine what grantmakers do, shifting them from being responsible distributors of funding for projects to investors and stewards of community infrastructure.

Grantmaking is not a zero-sum game. Money is not the only investment grantmakers can offer. Recognising this helps funders to work from a place of abundance, engaging with and supporting grantees in myriad ways. Working abundantly celebrates plurality and the knotty entanglements of the collective across ideas, people and the natural world. This will require creativity and experimentation. But those who are willing to take those risks, to experiment and learn, to bring ambition and courage, will be the ones making radical shifts in how they create impact. Grantmaking will be wiser, smarter, infrastructural and more ready to make the transformational changes we need right now.

Thanks for reading.

References and resources**

Andreotti, V., Stein, S., Ahenakew, C., Hunt, D. (2015). Mapping interpretations of decolonization in the context of higher education. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 4(1), 21-40. Retrieved from: https://decolonialfuturesnet.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/mapping-decolonization-he.pdf

Barbour, K. (2016) Embodied Ways of Knowing Waikato Journal of Education 10. 10.15663/wje.v10i1.342.

Basu, P., Tiwari, S., Mohanty J. and Karmakar, S. (2020) Multimodal Sentiment Analysis of #MeToo Tweets using Focal Loss (Grand Challenge), 2020 IEEE Sixth International Conference on Multimedia Big Data (BigMM), pp. 461-465, doi: 10.1109/BigMM50055.2020.00076.

Birhane, A. (2021, 12 Feb) Algorithmic injustice: a relational ethics approach. Patterns 2. Retrieved from: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0

Caldicot, L. (2021, 13 April) Where Power Lies: How lived experience is engaged in voluntary sector governance and decision-making. NCVO. Retrieved from: https://publications.ncvo.org.uk/where-power-lies/

Code, L. (1991) What can she know? Feminist theory and the construction of knowledge. New York: Columbia University Press

Constanza-Chock, S. (2020) Design Justice. The MIT Press. Retrieved from: https://design-justice.pubpub.org

De Jaegher, H. and Di Paolo, E. (2007, 5 Oct) Participatory Sense-Making: An Enactive Approach to Social Cognition. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences. 6:485-507

D’Ignazio, C. and Klein, L. F. (2020) Data Feminism. The MIT Press. Retrieved from: https://data-feminism.mitpress.mit.edu

Durden-Myers, E. J., Meloche E. S. and Dhillon K. K. (2020) The Embodied Nature of Physical Literacy: Interconnectedness of Lived Experience and Meaning, Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 91:3, 8-16, DOI: 10.1080/07303084.2019.1705213

Escobar, A. (2018) Design for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds United States: Duke University Press

Galton, F. (1907) Vox Populi Nature. (Vol. 75, pp. 450-451) Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1038/075450a0

Giggs, R. (2020) Fathoms: The World in the Whale

Gray, J. (2019) Data witnessing: attending to injustice with data in Amnesty International’s Decoders project,Information, Communication & Society, 22:7, 971-991, DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2019.1573915

Hallsworth, M., Egan, M., Rutter, J. and McCrae J. (2018, 11 July) Behavioural Government. Behavioural Insights Team. Retrieved from: https://www.bi.team/publications/behavioural-government/

Haraway, D. (1988) Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies. Vol. 14, No. 3. pp. 575-599

hooks, b. (1989) Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black. Boston: South End Press

Jamieson, L. and Lewthwaite, S. (2019, 4 March) Big Qual - Why we should be thinking big about qualitative data for research, teaching and policy. LSE Blog. Retrieved from: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2019/03/04/big-qual-why-we-should-be-thinking-big-about-qualitative-data-for-research-teaching-and-policy/

Kendell, G. (2016, 9 Feb) How to unleash the wisdom of the crowds The Conversation. Retrieved from: https://theconversation.com/how-to-unleash-the-wisdom-of-crowds-52774

Kyselo, M. (2014, 12 Sept.) The Body Social: An Enactive Approach to the Self. Frontiers in Psychology. Vol.5, No. 986

Mulgan, G. (2018) Big Mind: How Collective Intelligence Can Change Our World. United Kingdom: Princeton University Press

Mulgan, G. (2020) The Imaginary Crisis (And How We Might Quicken Social and Public Imagination) London: UCL. Retrieved from: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/steapp/sites/steapp/files/2020_04_geoff_mulgan_swp.pdf

Nadar, S. (2014) “Stories are data with Soul” - lessons from black feminist epistemology. Agenda. 28:1, 18-28.

Nagar, Y. (2012). What Do You Think? The Structuring of an Online Community as a Collective-Sensemaking Process. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW. 393-402. 10.1145/2145204.2145266.

Nesta Collective Design Playbook https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/Nesta_Playbook_001_Web.pdf

Parlovskaya M. and St. Martin K. (2007) Feminism and Geographic Information Systems: From a Missing Object to a Mapping Subject. Geography Compass. 1/3, 583-606.

Pentland, A. (2008) Honest Signals (USA: MIT Press)

Phillips, R. (2015) Black Quantum Futurism: Theory and Practice - Part One in Black Quantum Futurism: Theory & Practice. (Great Britain: Afrofuturist Affair/House of Future Sciences Books)

Rock, D. and Heidi, G. (2016, 4 November) Why diverse teams are smarter Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from: https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter

Surowiecki, J. (2004) The Wisdom of the Crowds United States: Doubleday

Tsing, A. L., Deger, J., Keleman Saxena, A. and Zhou, F. (2021) Feral Atlas (United States: Stanford University Press) Retrieved from: https://feralatlas.org

Varela, F., Thompson, E. and Rosch, E. (1991) The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Woolley, Anita & Aggarwal, Ishani & Malone, Thomas. (2015). Collective Intelligence and Group Performance. Current Directions in Psychological Science. Vol. 24. pp. 420-424. 10.1177/0963721415599543.

Yunkaporta, T (2019) Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World (UK: Text Publishing)