Week 7 - Insights from our interviews

This week we finished synthesising what we learned from the interviews we carried out. Here they are with supporting quotes alongside. We feel this is a pretty good summary of what we’ve learned so far. These will inform the prototyping we’ll do next week.

Ask good feedback questions

Getting good feedback on applications from peer reviewers means asking the right question. Asking for general “comments” doesn’t lead to good feedback:

On the portal there was a comment box attached to each application where they could record their comments. I don’t think anyone in my time used that.

Edge Fund ask peer-reviewers to consider how they feel about a project, on a scale of 1-10, with supporting sentences, for example:

“I feel very strongly that the application should be funded, i have no doubts about it all” - 10

“I feel strongly that the application should be funded” - 9 or 8

…

“I feel very strongly that the application should not be funded, I have serious concerns about it” - 0

“I don’t have enough information or knowledge to score this application” - X

The Other Foundation ask their peer reviewers to make two arguments when recommending an application:

How does it fit with The Other Foundation’s strategy?

How does it fit with your personal idea of change and what makes things happen?

Recommendations

- Avoid asking for an abstract score, or asking generally about what a peer-reviewer thinks.

Peer-reviewing can be onerous

Many of the people we spoke to described peer-reviewing as a formidable task!

At Camden Giving “the panel meeting is usually a really full on 3 or 4 hours with 5 minutes break every hour”.

A subgroup of peer-reviewers at The Other Foundation had 110 concept notes to review together, with Zoom meetings often running on into the evenings.

Rose explained how a particular funding stream at FundAction was supposed to be open twice a year, but in reality has become annual as the participatory process is quite demanding.

Grouping and categorising applications helps

All the funds we spoke to categorised or grouped their applications by theme.

This might be done by fund staff:

We’d download the applications, categorise them somehow, make it a bit more easy to understand if there’s a pattern, or a theme. Have we got 10 applications focusing on homelessness, for example.

Or it might be done by participants themselves:

I also vaguely kept track in my mind of categories. There were a lot of Christmas applications and a lot of COVID support applications. We knew we ultimately had to rank our top 5 in order and I didn’t want our 5 projects to include more than 1 Christmas or more than 1 food aid application.

I’d be like ‘why have we got 5 proposals from Serbia out of 25?’ Unless there’s something that I think is really important and interesting I’m going to prioritise the Czech republic.

At FundAction, the people writing the applications would ‘tag’ them with one or more particular themes.

We learnt how both FundAction and The Other Foundation categorise proposals to help ‘balance’ how funding is distributed.

We want a balance, different thematic areas, regions and identity spectrum.

We have targets for the regions, we don’t want to give too much to one region

It’s not a technical process, not a bureaucratic process, it’s a soft process to get that balance

Samuel also told us how he used a spreadsheet to visualise how money was being allocated to different categories. This meant that in real time you could see how a decision to fund a particular project impacts on the balance across the fund as a whole.

They [the peer reviewers] would meet amongst themselves and discuss who do we think should get funding? They might say ‘look, we’ve got 10 proposals here but 4 are from Spain. We can’t fund all the things in Spain.’ Or people would say ‘we’ve got 10 proposals but only 1 of them is addressing economic justice which is something we think is important so we should push this forward’ or whatever it is.

Categorising proposals also helps ensure relevant people make decisions about them.

Edge Fund has a series of ‘council groups’ of people with specific lived experiences. They review the proposals that impact on their community. They have the power to adjust the proposals’ scores:

It’s about valuing lived experience.

We have these groups which are race and ethnicity, LGBTQI, environment, systemic, gypsy traveller and roma, women & oppressed genders, working class communities, health & disability.”

Each council group will check and see if they pick up on something. So quite often, for example, a white man might have no concept of some of the issues faced by African community. So in order to mitigate missing, or getting it wrong, we have these councils. So disabled people, look at disabled applications, etc.

The Other Foundation form similar groups:

Thematic area wise, we need a balance so that a religious application is seen by someone in that area, so that the necessity of the project is seen by someone with that perspective.

We also learnt that if The Other Foundation receive an application and they feel that they don’t have someone with lived experience to review it, they will actively seek out someone.

We heard how this matching also helps Camden Giving identify applications with genuine local knowledge:

It was very clear to our panelists that sometimes they [large national charities] were relying on statistics rather than actual conversations they had with local people.

We also heard how Stretford Public Hall recognise the value of segmenting their community based on their interests:

We’re segmenting, we’ll know if people are particularly interested in wellbeing, we’ll send content around that.

A digital tool could offer the opportunity to log what ideas participants engage with and in turn use this to recommend things they might be interested in in the future.

Recommendations:

- Make it easy for people to see applications that are relevant to them.

- Encourage peer-reviewers to think about their lived experience of the issue (as opposed to second guessing how a funder might evaluate a project).

Ordering applications introduces bias

We learnt peer-reviewers wouldn’t always have read all the applications before coming together. Panelists often had busy lives with other responsibilities like work, school and childcare.

Some do the readings, some don’t. You do give space in the week for those kinds of deliberations. And people get started, it starts to flow, they start feeling uncomfortable not having read everything and so they catch up quite quickly.

Sometimes people might read 75% of the applications we received and by the panel meeting perhaps they didn’t have enough time to read all of it.

We learnt how people would often review the proposals in a set order:

We’d always go through the applications alphabetically because that’s how it’s displayed on the portals.

[We] each worked through our own set of applications in numbered order.

Ordering like this can introduce bias, as the proposals at the end inevitably get less attention than the first as the reviewers tire.

We saw how FundAction’s portal had attempted to overcome this, but also how it proved annoying in practice:

there’s this extremely annoying system where Decidem randomises the proposals that you see every single time you go to the proposals web page. So they’re not alphabetical or anything like that. The intention there is you’re not just getting through the top ones and get bored. You read a wide range of proposals.

Recommendations:

- Randomise the order of applications for each reviewer so that not everyone ignores the same set of applications.

- Display ideas in a random but common order on web pages that rotates. This means people can say things like “the idea on the home page” and know they’re looking at the same thing, but that this will change over time.

- Make it easy to search for proposals, so if you’ve seen something in the past, it’s easy to find it again in the future.

Make it easy for peer reviewers

Peer-reviewers are volunteering their time to review applications and so it’s important to make the most of this.

At Edge Fund the Admin team do a first pass through all applications ensuring they are eligible. This means the wider membership don’t waste their time looking at ineligible projects.

At Camden Giving fund staff would summarise the applications and compile a spreadsheet for the peer-reviewers. This helped them understand the projects as a collection, how much money is available in the fund, how much is being applied for and what the difference is.

On Edge Fund’s voting day, the facilitation group focus on making it a relaxing, participatory experience:

It all happens in a very grassroots meeting place. […] We tend to cook, members volunteer to cook and clean. I was on duty putting out pots of tea and drinks and all that sort of thing.

Liverpool SOUP organisers would remind panel-members to get their feedback in during the run up to an event by sending them emails. This is useful as they recognise their panel-members lead busy lives.

Recommendations:

- Automate email reminders as deadlines approach (don’t expect people to come to your website)

- Present applications inline with categories (not on separate spreadsheets)

Complexity in decision making

All of the people we spoke to explained there were key stages as to how their groups made decisions over time:

For FundAction, it looked like this:

- Open call for ideas (~2 weeks)

- Deliberation (~2 weeks)

- Voting (3 days)

Edge Fund facilitates a day where members and applicants come together to vote on which applications will be awarded money. Isis explained that the day looks like this:

- Meet one another, learn about projects (morning)

- Have lunch, reflect on ideas

- Vote (afternoon)

Gerry told us how developing a Neighbourhood Plan has a clearly defined set of stages, which a plan must pass through, but may stop along the way.

Explicit stages like this help people participating in the decision making know exactly where they are in the process and what’s expected of them. They also can see ahead what the impact of their involvement will lead to.

Recommendations

- Demo the decision-making process (don’t simply explain it). Tech provides an opportunity to demonstrate how something works in situ. For example, when using Slack for the first time, you’re invited to have a conversation with Slackbot. You start learning your way around how it works.

- Clearly explain the stages in the decision-making process. A website provides an opportunity to be dynamic in this. It could show what stages have passed, what the results were, and what happens next.

Outsiders trying to understand a process

It’s important to clearly explain how participatory grant-making works to potential applicants, peer-reviewers and the wider community.

It’s good practice to explain what sorts of projects a fund might support. Everyone we spoke to published examples of previous people or projects they’ve funded. We saw how Edge Fund also publishes their funding values and explains how the members make decisions.

While some applicants may have had experience applying for funding, we heard that with PGM they may not appreciate that it isn’t the funders making the decisions, but people like themselves.

We’d constantly remind applicants we’re not the ones making the decisions.

I fear a lot of people don’t read the blurbs at the top of these application forms, but it’s very clearly pointed out that we’re a peer-review process.

The Other Foundation offers comprehensive guidance on how to apply, publishing guidelines for how to complete ‘concept proposals’ and ‘full proposals’.

Recommendations:

- Clearly communicate the criteria by which funds will be awarded.

- Consider publishing successful and unsuccessful applications and feedback in full.

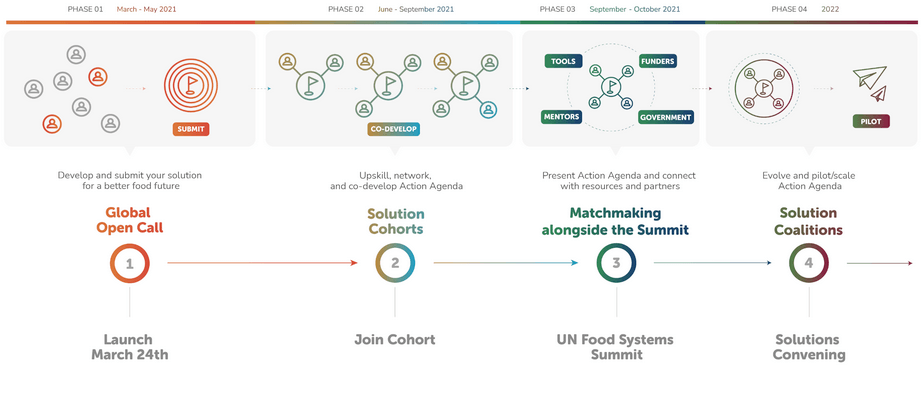

- Clearly communicate the process of participatory grant making, (e.g. see how Open Ideo explain the stages in their design briefs):

Feedback & improvement

All the funds we spoke to operate in cycles of grant giving. This means that each time a funding round finishes, it offers the opportunity to learn what went well and what could be improved for next time.

“Every single year, every single process is reviewed and changed so it’s iterative.

Basic principle remains the same. After every round there’s a review process where we get together, make changes, take onboard feedback. Make tweaks here or there.

We heard how members of the staff team at Camden Giving would hear participants talk about the sorts of things they’d like to see funded in the future:

They’d say ‘I would really love to focus on drama and arts for young people’. As a team we’d think about how we can fundraise to create a fund to focus on the arts.

The rounds also provide an opportunity to see how well the fund is reflecting the priorities of the community it aims to serve. Every 2 years The Other Foundation hosts a community gathering called a Kopano. This gathering is a chance to assess how the fund is working to support the community and set the strategy for future funding rounds.

We also learnt how Carbon Co-op have space on their community forum explicitly for feedback on the site itself.

Recommendations:

- Encourage participants who engaged in the collective decision making process to share what they thought of it.

The practicalities of coming to a decision as a group

We heard lots about how groups make decisions together.

No fund approached their group decision-making in exactly the same way. Often sub-groups within the funds would even take their own approaches too.

From our interviews, we’ve created two idealised ‘journey maps’ of how a PGM fund works:

- Journey map inspired by Camden Giving and The Other Foundation.

- Journey map inspired by Edge Fund and FundAction.

Who decides how to decide?

We heard how Samuel and the peer-reviewers together decided how to deliberate about the projects in the last round:

So what number are we talking to? We’d go through each one, if there was a hard Yes or a hard No, or a maybe, so we’d put it aside if money was still available. Things like that, so very broad discussion. I know other groups would do ‘everybody bring to the table their top 10’. And from there, we’ll just discard the ones that weren’t in anyone’s top 10 and then discuss the top 10s to whittle it down to a more appropriate size. Very much up to the programme officer based on what they receive in front of them

Similarly peer groups at FundAction would decide amongst themselves:

They would then talk about what criteria they’d use and what questions they’d ask applicants. Because every time they might have some different concerns or interests

And they would also decide how they were going to do the decision making. Will we vote? Try and do it by consensus? Anonymous?

At Camden Giving the fund staff suggest the way an individual vote becomes a group decision. They used a consensus decision-making process whereby a vote would take place after staff shared a summary of each application and after people shared their viewpoints.

If it was a majority yes it would be a yes straight away. If it was a mix or split, we’d put it in maybe.

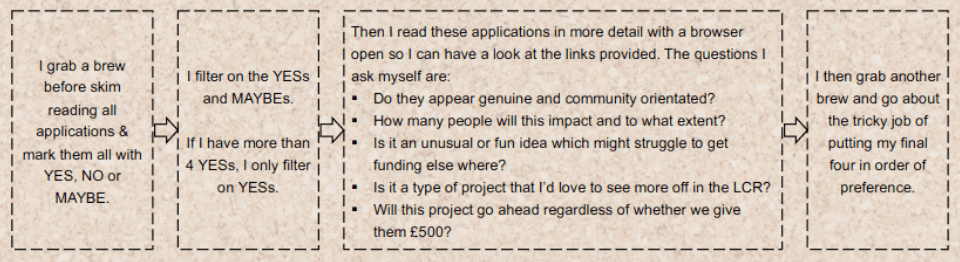

Liverpool Soup’s organiser offers guidance to panel members by describing their own approach:

Common principles when deliberating face-to-face

Some principles emerged that were common across the people we spoke to about face-to-face deliberation meetings:

Everybody has a voice

Making sure everybody speaks, everybody has a voice, everybody feels comfortable with the decision that was made before we move on.

Every proposal is considered

We would go through every single application…

When we felt they had enough time to have a conversation about it we would use the poll option on Zoom and they would [each] say yes, maybe or no.

But for me the best way to work it is go through every single one: yes, no, maybe. Get to the end, go through them again. Make sure your arguments are strong.

It felt important to go back through the ‘Maybe’ to just discuss each one together to make sure we hadn’t missed something.

Tech for decision-making

Software formalises and encodes a decision-making process.

Beyond Google Docs, Zoom and Spreadsheets (see Tech obstacles), we learnt how Edge Fund built an “Assembly” website. It supports members to debate ideas, make proposals and find out when meetings are happening. They’re using a customised version of Decidim.

When evaluating digital platforms for collective decision making, Engage were looking for something that allowed various levels of engagement (thumbs up/down, comments, new ideas) for their consultation work. They settled on Your Priorities.

We learnt that 15-30% of Edge Fund’s members review and score applications each round. This is similar to about 20% of FundAction’s membership who vote each round.

Recommendations:

- A digital tool could help capture individual Yes, No, Maybe votes and present group votes, e.g. Yes / Yes, Yes / Maybe.

- Provide guidance to what you’re being asked to do ‘in-line’.

- Visibly show how many votes you have available.

- A digital tool should offer various levels of engagement.

Give people something to respond to

In my experience the most useful tool is having existing stuff, whatever that is, to be built on, when you’re doing community consultation type stuff. I’ve found in various roles […] if you just ask something a very open ended question like “do you have feedback?” or “what’s your opinion?” you don’t get anything.

We saw Louis’ observation echoed in our other interviews.

Engage found that encouraging people to work on maps worked well in workshops designing Neighbourhood Plans. They provided a practical way for residents to start talking about issues of belonging and identity.

Stretford Public Hall wanted to know what sorts of activities people would like to see in their newly renovated ballroom. To spark peoples’ imaginations, they provided some interesting examples.

Building solidarity

We saw how participatory grant-making is explicitly about building solidarity within a community.

Part of the reason we bring people together for the funding round is to bring solidarity so groups can work together, support each other.

They then know each other really well. You’ll have some anti-corruption activist from Romania end up super super bonding with some housing-rights activist in Spain, which you wouldn’t get. I know racial-justice person in London that ended up staying in Serbia for a winter because they met people during this process.

By working together, we learnt how solidarity can be built by understanding what’s important to people different from yourself:

FundAction wanted to re-create this sense of building solidarity. More so than any other grantmaker, both were established with the intention of building cross-movement intersectionality. Intention is to understand each other’s struggles.

We’d also like you to include a variety of project types in your final four, this is beneficial as it enables us to teach our audience about a larger range of topics which are important to local communities.

- Advice to Liverpool SOUP panel members

There was a time when a group of people of African heritage wanted to get funding for this drumming that they do. It’s political, they go along to demonstrations, it’s part of our culture. Someone, a white guy, said ‘I don’t think we should be funding drumming lessons’ which was a complete misinterpretation of what it was. But because we had a group of people of African heritage who understood, no this is not drumming lessons, the score was adjusted and this group got funded.

At the point of awarding grants we’d always encourage grantees to let us know if there’s any exciting events happening so we can share with them the panel.

Recommandations:

- Ensure tech supports people in communities to build solidarity with one another

Simplify application

There was a lot of variation in the size of the application process at different funds. Some asked for pages of written information and others asked for lots of accompanying documentation upfront.

Everyone talked about the importance of simplifying applications. There was an acknowledgement that applying for grants is overly complicated.

I think it’s a major issue in the funding sector … because we’ve developed all this language and ways of working that’s just not accessible whatsoever.

Ask a small number of questions

Both FundAction and Edge Fund made a point of keeping the questions very minimal on the application:

There’s 300, 500 words. In my opinion that’s at least as much information as you need.

The proposal isn’t complicated, what it is you want to do, why you want to do it, who you are, how much it’s going to cost roughly and that’s about it.

…a set of questions and a limited amount of response required. It’s very, very simple. That’s one of the changes. The application’s got shorter and questions have changed according to feedback as well.

The Other Foundation’s concept notes are longer but there’s still an emphasis on simplicity.

It’s 7 pages but it’s 7 very directed pages. We simplified the form to be very much, what are the activities, what are the outcomes, who are you working with? And try to keep it as simple as possible.

Recommendations

- Ask one or two short, clear questions.

Provide guidance inline with application

We heard about application forms being accompanied with guidance documents.

There’s another document, guidance. The guideline gives you a very clear explanation of what we’re asking and why we’re asking and what the role is.

Could this be a hang-over from the days of printed applications? Referring to printed guidance alongside a printed application is convenient. Today, on a mobile it’s highly inconvenient to switch between two different documents.

Recommendations

- Consider why guidance is necessary. Could the questions be simpler or clearer?

- Provide guidance inline, alongside the question so it’s available at the point of need.

Due diligence can happen later

Some funds ask for due diligence information as part of the application.

We’d ask for their constitution, bank statement, safeguarding policy [upfront].

We also recognised that some groups are tiny and don’t have capacity to share this information at the point of applying. We would give applicants anopportunity to submit placeholder documents (usually a blank word document) to give them plenty of time to organise their paperwork. If a grant is awarded to an organisation, we would not release payment until we received all the due diligence documentation.

Similarly, others split the application by asking for an initial “concept note” or “proposal”. If peer reviewers select that concept note, then they provide the due diligence information in a second stage.

So the reason we do concept notes is we don’t want people wasting their time. …

And then you can have a conversation and follow up. The peer to peer panels shouldn’t be asking for loads more, especially written information.

Recommendations

- Consider what due diligence information is actually required. How will it add to the peer reviewers’ judgements?

- Do due diligence after peer reviewers select a proposal. Don’t waste everyones’ time asking for documents that might never be needed.

Requirements can be simpler for smaller funds

Many funds have different sized grants and we heard that smaller funds can have simpler requirements than larger ones.

…unless it’s a tiny grant, we have less requirements, bigger grants we have more requirements.

…it’s at that point that everything ends. The top 5 or 10 voted grants are just the ones that get the money. It’s smaller money. It’s like 5K, OK the people have voted, done.

Detailed budgets can cause trouble

We heard about different issues that arise from asking applicants for budgets. Peer reviewers could get caught up on the details of the budget, potentially distracting from their real expertise from lived experience.

So the very first one we did, we had budgets and everything attached to these concept notes.. And the peer-reviewers got very stuck in that. “No you don’t need £70K, you need £60K for this”. And we wanted to remove that. We wanted peer-reviewers talking at a strategic level: “Is this a good idea?” We’ll do the due diligence, the budgeting and all that later.

…our panelists would really love to look at the budget and figure out if its… If anything our panelists were super careful. How do we ensure we give enough confidence to the panelists where they don’t feel like they need to code switch and become a traditional funder. Actually what we’re asking them is to bring their knowledge and expertise and analytical skills and that’s it really.

Detailed budgets also cause trouble when things inevitably change. An overly specific budget is inflexible:

Because what happens a lot of the time is grantees get very nervous that we care about the budgets and make very small line item choices, but that messes us up in the next phase of monitoring it because later they want to change it and you need a whole approval process to do that.

When there’s a fixed sized pot of money, asking for specific budgets can also lead to administrative overhead if the applicant applies for less money:

Several times folks have pitched for less because they need less, but to be honest that’s kind of annoying because you have this random bit of money outstanding. It would be easier in future just to say, this is the amount, don’t bother with a budget or anything like that.

Recommendations

- Consider whether asking for a budget is actually necessary.

- If necessary, ask for a rough budget to stay flexible and save everyone time.

- Be flexible about budgets changing after they’ve been written.

Some funds help with digital

We heard about funds helping people who are less able to complete a digital application form. They help with the application form or even write it for them.

They can also arrange to speak to one of the regional organisers. People would ring and ask questions. Also if someone has a language barrier, we can arrange for someone to speak their application and have it written up for them.

There were a bunch of young people who were interested but hadn’t applied. We also had some time to help them actually submit the application form.

Transparency

Transparency among members was a central theme at FundAction. Within their closed, private group of members, all members can see most of what goes on. They can see all applications, deliberation is done openly and everyone can see how many votes each application got.

At the end of the voting period the facilitation group - and everyone I think - can see which proposals out of the 25 got the most thumbs up, the most votes… It’s all on the platform, everybody knows.

For FundAction, feedback to applicants is automatic as a side effect of the transparency:

Because on the platform people would’ve already got feedback because of the voting and the public comments.

In contrast, at Edge Fund, feedback is available but must be collated manually on request:

Yes basically, if anyone requests to see that it can be all shared. Say organisation XYZ asks why didn’t I get shortlisted? Then a regional organiser can go in to that document, get that information up, pull up all the comments, collate them and send them to that group so could see why.

While The Other Foundation made the decision not to give feedback to applicants at all:

We don’t give any feedback. Peer reviewers want us to give a lot of feedback, but we don’t give any feedback.

- Samuel, The Other Foundation

Even at FundAction, transparency is not absolute. All members vote on applications to select the top 5 or top 10. Although everyone can see how many votes, they can’t see who voted for what:

You can’t see who voted for what… a lot of people know other people on the platform. You wouldn’t want it to be open because then, that might damage the friendships if you didn’t vote for that proposal.

For larger grant amounts the process extends after member voting. A randomly selected peer group takes the top 10 applications and selects 5. Their decision making happens in private which has been a source of tension:

This whole [peer group] deliberation, discussion, interviews, final decision-making all happens outside member scrutiny and the platform. This was contentious. There were many people that felt the process should be accompanied by a rapporteur basically who was reporting to the rest of the community.

A solution they’ve used is to have a public and a private version of a document:

One of the ways we did that was to have two Google Docs where one would be closed and that would only be for the peer review panel. That would be for their notes, their private conversations and that’s where [the facilitator] recorded disagreements, discussions …then that was then summarised and the outcomes were shared publicly on the platform.

Carbon Co-op operates transparently in order to stay close to their members. As well as hosting regular events, they consult regularly with small groups of members. They recently started a forum for staff and members to talk directly to each other.

Created the community forum, place for members to interact, for us to bounce ideas off the members, share aspects of what we’re doing… We don’t want what we’re doing to be really detached and a surprise to the members.

Recommendations

- Consider defaulting to transparency. Ask “What’s the reason we shouldn’t publish X?” rather than the reverse.

- Collect data (comments, voting) in a structured, digital format.

- Automate publishing of feedback to save staff effort, increase trust and help community members learn and understand how to improve applications.

Pros and cons of video meetings

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, we heard a lot about the switch to video meetings. Although challenging, there were unexpected benefits.

We heard that video meetings actually increased turnout at events:

We do get quite good turnout at the AGM. Virtual AGMs are a really good innovation that has happened because of the pandemic. They weren’t being done virtually, so you were only getting the people who were willing to come out on a wet Tuesday evening.

If anything having online events, across the board we’ve had a much higher number of people getting involved.

While video calls work well for one-to-many type meetings, they were more challenging for many-to-many meetings like decision-making. In that case, it took longer and required very careful facilitation:

It takes a lot longer to do it virtually. Because you don’t have that sort of quick engagement that you can do. You have to let everybody speak to each application as opposed to, I don’t know, you miss out the small things of nodding and things like that. … making sure the facilitation was a lot more … certain. Making sure everybody speaks, everybody has a voice, everybody feels comfortable with the decision that was made before we move on.

Poor internet connections caused problems too:

Videos help a lot, but a lot of the time people didn’t have very good reception and things like that… it takes a lot of data to use Bluejeans, we weren’t as conscious about our technical spaces.

We heard about groups using screen-sharing, Zoom’s poll feature, and breakout groups:

_We would use the poll option on Zoom and they would [each] say yes, maybe or no. _

Over Zoom, we would share a screen and one of the team members would be scrolling.

We used a terrible video conferencing thing, Bluejeans. Annoying beyond belief. We didn’t have breakaway groups.

It didn’t always work out, with groups telling us they used WhatsApp as a backup, or in addition:

Out of frustration at other technology we often ended up using WhatsApp calls. Where we would talk through. Everyone had access to that easily and had experience using it.

One interviewee felt they should continue using Zoom to supplement face to face in the future:

I said to the team, once Covid-19 is over we should still use Zoom for people who can’t make the meeting in person. We should revert back to meeting in person but if someone can’t make it we should give them the option of joining on the big screen.

Tech obstacles

We listened especially carefully for areas where use of tech might be creating obstacles for applicants, peer reviewers and staff.

We heard a lot about Microsoft Word documents, Excel spreadsheets and PDF files. Funds commonly provide a Word template for applicants to download, populate with words, then return by email:

The applicant will get a Word document, and then either we’ll turn it into a PDF or they’ll turn it into a PDF or we’ll send it on as a word document.

- Samuel, The Other Foundation

The words are then - manually - extracted from the Word file within an email and entered into an Excel spreadsheet:

One that’s done, it’s put into a spreadsheet and it’s all collated. Then it’s sent out to members to longlist.

We enter all those applications onto an Excel spreadsheet

We would send them an Excel spreadsheet document and then the team would use [a single shared] OneDrive Excel sheet.

We heard about Word and PDF files becoming surprisingly huge, making them difficult to open:

People copy content from their website into the Word form and they’d get the formatting stuff so the file size would be 5mb. And peer reviewers would say, “I can’t access this one, I can’t access that one?”

I had a couple of issues with the email. The first was that the shortlisting PDF had a 22MB image background so I couldn’t open it on my phone and it was really slow to open on my computer.

More broadly, Word, Excel and PDF files are unsuitable formats for mobile.

They have to have a computer or access to a computer to be a peer-reviewer.

Alternatively, reviewers are asked to create an account on a “portal” containing all the applications:

We set up user accounts using their email address [in Salesforce] and we’d send them a link and they’d set up a password. They’d read the applications on the reviewer portal via Salesforce.

They would have to login to this website and they would have access to everything we had access to, so the application form, the due diligence documents, all of it.

The problems with Word files are compounded by the classic versioning problem: different versions of documents being sent back and forth. Funds actively encourage back and forth of applications:

I try and encourage a back and forth - I say “please send it to me before the deadline so we can do back and forth”.

Even FundAction felt their platform, which is highly customised, was creating barrier:

…how the digital platform could make life easier. Because I do think that that is a barrier to engagement.

Recommendations

- When sending peer reviewers applications, use a mobile-friendly web page. Avoid Word, Excel and PDF files.

- Allow peer reviewers to review applications in several short sessions using their phone, rather than one single session at a computer.

- Make applications print-friendly for peer reviewers that prefer to use paper.

- Incorporate collaborative editing tools into the application process rather than treating applications as a one-shot process. Examples are Etherpad and Google Docs.

- Don’t require people to make an account or choose a password. Authenticate based on email.

- For spreadsheets and documents, use a single shared instance in e.g. Google Docs or OneDrive. Avoid emailing copies.

Growing and caring for the community

Grant-makers and community organisations need a community of panelists, applicants and members. The organisations we spoke to value a diverse membership and use a variety of ways to reach new people.

Finding new members

Carbon Co-op host meet-ups and webinars about home energy and low carbon topics. They find that these free events attract the kind of people that may go on to become members.

People come in through attending our free webinars and are supportive of the direction and approach we’re taking

Most groups promoted things through their website and social media. Notably, Edge Fund told us they don’t tend to use Facebook any more.

We also have about 300K followers on Facebook. Facebook is by far our biggest platform for communication with our community.

It would be launched on Decidem but also emails would go out to members, on social media etc.

Many recognised the limitations of relying on broadcasting with a website and social media:

We’d advertise the role on our website and on social media. We’d also utilise our local connections. If you just have something on a website that’s really passive, that’s assuming they visit your website or they follow you on social media and that’s not necessarily the case.

The Other Foundation used specialist software called DevMan to promote opportunities to a list of around 15,000 people.

Furthermore, they actively reach out to people they think are doing good work. They even put their pride aside and encourage critics to become panelists!

We’re going to groups that we know are working and having an effect. We’re constantly engaging them around support, partnerships and how we can help.

When people shout at us about being bad funders, we want to bring them into those spaces, because those are the people we want in those spaces.

Edge Fund attracts suitable applicants by printing flyers and handing them out at physical protests.

Engage Liverpool uses flyers too, delivering them to every household in an affected region.

FundAction grew their membership through using the connections and judgements of existing members:

[Members were] given 5 invites each. We all invited people that we knew that we thought would be good for the community.

Being considerate

Edge Fund work hard to include people, ensuring that cost of travel or disabilities don’t prevent people from participating:

Travel, we pay for travel to come. If people need access costs or support, someone to come with them, we pay for those costs as well. Interpreter, that sort of thing.

Carbon Co-op recognise the importance of their membership. They recently created a new role whose job includes working with members:

A large part of my role is dedicated to working with the membership. It’s not that that hasn’t always been a part, but there was no-one directly responsible before me. I’ve spoken to a lot of members, chat with new members, ask them why they joined.

Engage Liverpool is thoughtful about making it easy for residents to participate. They plan meetings at a convenient time and place for people to attend.

Always on an evening, people have come home from work. Any places close to where people live that would make their space available.

Edge Fund recognises the importance of a varied membership for continually improving their organisation:

Always up for conversation. We’re not set in stone. That’s why our membership has to be varied.